Anthony Albanese will go down in history as Australia’s worst Labor prime minister when it comes to economics.

That is no exaggeration, nor is it a case of talking down whoever is in power to get a headline.

While inflation has moderated under his watch – and in the rest of the world – he is the only post-war Labor leader to lack a sense of purpose and leave no lasting legacy that will benefit future generations of Australians.

His plan to double taxes, to 30 per cent, on superannuation balances of more than $3million is nothing more than a revenue grab.

Labor’s Future Made in Australia is little more than a very expensive subsidy scheme masquerading as a concern about climate change.

Clumsy attempts to regulate social media companies just demonstrate the stupidity of his government interfering with freedom of speech without making the country any safer – just to look busy.

And record-high immigration levels above 500,000 per year, during a rental and housing affordability crisis, prove he leads a government addicted to income tax revenue from bringing in more skilled migrants.

He has shown no desire to reform the tax system to fix this structural, economic problem that has stopped middle and average-income earners from being able to buy a house and have sufficient savings.

Other than to have the government buy a 40 per cent stake in a new house with first home buyers under Labor’s new Help To Buy scheme – which would only push up prices further and waste even more taxpayers’ money without addressing the root causes of unaffordable housing.

Unlike other Labor PMs, Albanese’s first – and perhaps only – three years in power would have brought about no structural change to the economy that improves living standards.

Which is a pity because Australians traditionally elect Labor governments to change things for the better, to benefit working class voters – even if the Coalition wins more elections.

The contrast is stark with Labor leaders since the end of World War II.

Ben Chifley, a former train driver from country Bathurst, was the last Labor prime minister to win the yes case at a referendum.

His 1946 campaign to give the commonwealth the power to legislate social services meant the federal government rather than the states would in future provide unemployment benefits.

The idea to amend the Constitution attracted 54 per cent support nationwide and was carried in every state, meaning those without work would get the same level of help wherever they lived and government resources would be more efficiently distributed.

Under Albanese, the Voice referendum to create a race-based, constitutionally-enshrined body of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives garnered less than 40 per cent support in 2023.

It was defeated in every state and territory, except the Australian Capital Territory, with no Labor solution since then to tackle Indigenous domestic violence, early deaths and welfare dependency.

Gough Whitlam may have presided over 17.7 per cent inflation and led a government embroiled in a scheme to borrow billions of dollars via a dodgy Pakistani commodities trader, Tirath Khemlani.

But his government’s 25 per cent reduction in import tariffs in 1973 was an idea embraced by both sides of politics decades later – leading to cheaper consumer goods for all Australians in the years that followed.

His establishment of Medibank in 1975, while abolished by his Liberal successor Malcolm Fraser, was revived as Medicare, with both major parties now backing universal healthcare so everyone can afford to visit the doctor.

Not to mention the fact Gough officially scrapped the white Australia policy and introduced no-fault divorce before being controversially sacked in November 1975.

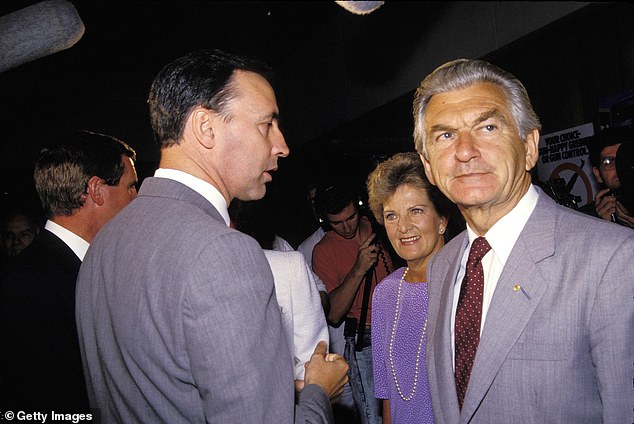

Bob Hawke in 1984 established Medicare and sex discrimination laws in his first term, and also floated the Australian dollar in 1983 so the government no longer needed to intervene in currency markets on a daily basis.

His successor Paul Keating’s first three years in power saw the Reserve Bank of Australia given independence to set interest rates without political interference.

Since that 1993 decision, Australia has never again had double-digit inflation coinciding with double-digit unemployment – leading to an ugly situation known as stagflation.

While unemployment was high during Keating’s time as PM, the introduction of enterprise bargaining to replace centralised wage fixing meant Australia would never again have a wage-price spiral that fed inflation.

The Albanese government so hates Keating’s legacy it has revived multi-employer bargaining – ignoring the lessons of economic history when the militant Amalgamated Metal Workers Union in 1981 took strike action.

This flowed through to the rest of the economy with average, full-time wages soaring by 14 per cent as inflation climbed by 11 per cent.

Keating in 1992 also gave Australia compulsory superannuation so people could retire with dignity – something Albanese should think about as he raids retirement savings in a bid to raise $2billion a year.

Even Albanese’s former Labor bosses, while mediocre, will leave a modest legacy.

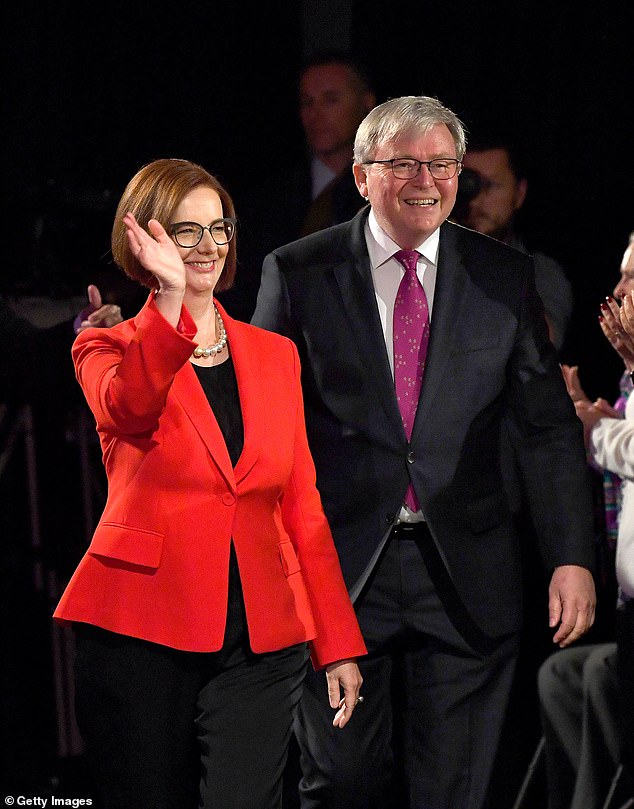

Kevin Rudd, who governed during the Global Financial Crisis, at least introduced per unit pricing at supermarkets in 2009 so consumers could have a better idea if they were being ripped off.

While Julia Gillard’s hated carbon tax was scrapped by the Coalition, her government at least legislated the National Disability Insurance Scheme in 2013, which while costly, gives dignity to many people facing physical and mental challenges.

Unlike previous Labor prime ministers, Albanese is addicted to temporary Band-Aid solutions designed to address political liabilities rather than solve problems long-term.

His temporary $300 electricity rebates to bring down headline inflation was a policy designed to counter Labor’s 2022 election promise to bring down power bills by $275 by 2025.

The Reserve Bank isn’t convinced and sees inflation climbing from 2.8 per cent now to 3.7 per cent by the end of next year, meaning a delay in rate cuts as the consumer price index again again strays outside its 2 to 3 per cent target.

Albanese’s Labor predecessors looked at ways to permanently fix structural economic problems but this prime minister cares more about the short-term politics or empty symbolism.

It’s hard to imagine any policy idea of his that will make life better for Australians decades from now whether he wins or loses the next election due by May next year.