They were one of the most advanced societies during the Bronze Age more than 5,000 years ago.

But the ancient Indus people – native to modern-day Pakistan and Northern India – left behind an ancient writing system that is still confusing experts today.

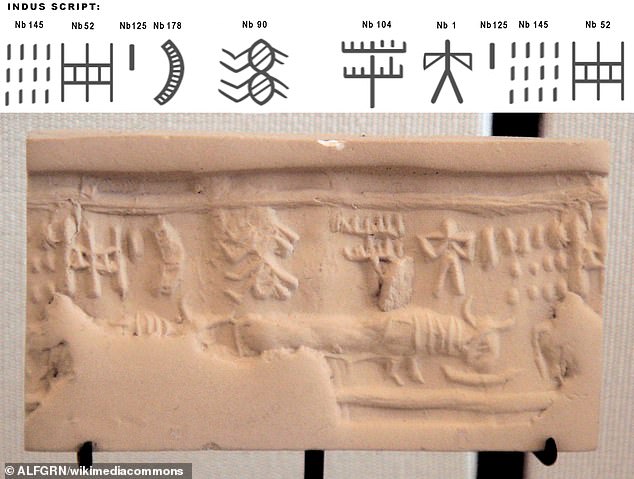

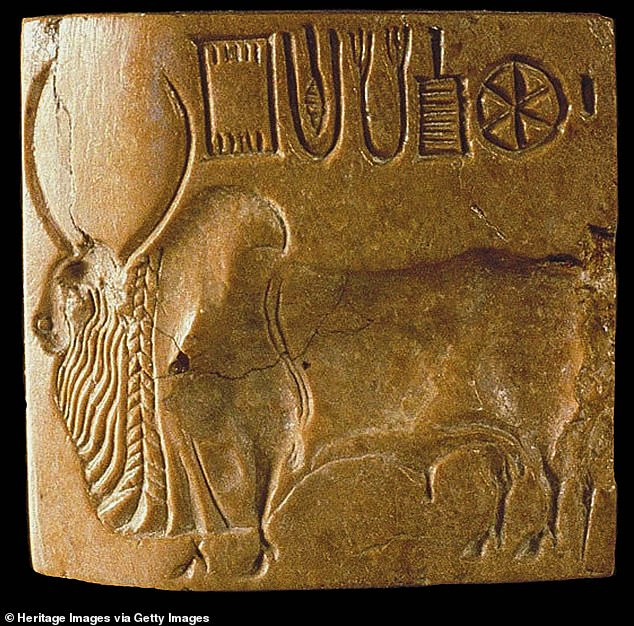

About 4,000 ancient plates, made of materials like stone and copper, are inscribed with the mysterious script.

It consists of odd letter-like symbols and illustrations, and is unlike any other language in the world.

Now, the Indian government is determined to finally decipher the ancient writing system.

It has announced that it is offering a whopping $1 million (£800,000) award to anyone who can crack the mysterious Indus Valley script.

‘I announce a cash prize of $1 million to individuals or organisations that decipher the script to the satisfaction of archaeological experts,’ said minister MK Stalin.

So, do you know what the letters and symbols mean?

The Indus – the largest yet least known of all the first great urban cultures – thrived from 2600 to 1900 BC, and then abruptly vanished from historical records.

Very little is known about the people, who strangely left no archaeological evidence of warfare and communicated in one of the world’s most unusual scripts.

Like their contemporaries, the Indus – who may have made up 10 per cent of the world’s population – lived next to rivers, owing their livelihoods to the fertility of annually watered lands.

In a statement, MK Stalin, chief minister of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, announced the prize to anyone who can successfully decipher the Indus Valley script.

‘We have not been able to clearly understand the writing system of the once flourishing Indus Valley,’ he said, quoted by Hindustan Times.

‘The riddle hasn’t been answered for the past 100 years despite several efforts by archaeologists and experts.

MailOnline has contacted the Tamil Nadu government and the Indus International Research Foundation about how to take part in the challenge.

It’s unclear if there’s an online process for hopefuls who think they can translate the script, or if the minister is expecting them to get in touch.

The Indus inscriptions – made on slabs of stone, bronze, copper and more – feature a mix of symbols and human or animal motifs, like bulls and unicorns.

Unfortunately, each slab has rather few symbols, making the challenge of trying to decipher what they mean especially hard, according to researchers.

The average length of the inscriptions is around five signs, while the longest, inscribed on copper, is only 34 characters long.

Some experts question whether the symbols represent a language at all, or are merely pictograms that bear religious or political symbols.

Although we don’t know what their inscriptions meant, we do know some details about the Indus civilization, also known as Harappan, which flourished for half a millennium in the area of modern-day Pakistan and Northern India from about 2600 BC to 1900 BC.

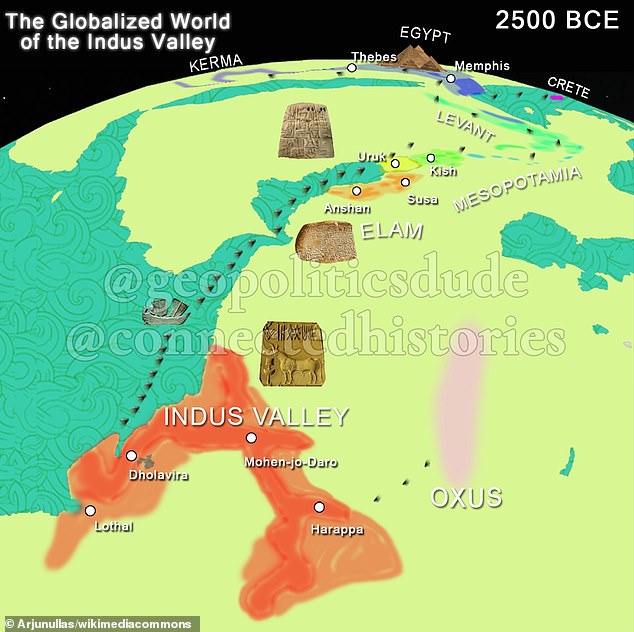

It stretched more than a million square miles across the plains of the Indus River from the Arabian Sea to the Ganges, over what is now Pakistan, northwest India and eastern Afghanistan.

But it mysteriously declined and vanished and remained invisible for almost 4,000 years until its ruins were discovered by accident in the 1920s by British and Indian archaeologists.

So far, more than 1,000 Indus settlements covering Pakistan and northwestern India have been discovered, including its two main hubs – Mohenjo-daro and Harappa near the Indus river.

Among their settlements, researchers have uncovered the world’s first known toilets, along with complex stone weights, drilled gemstone necklaces and exquisitely carved seal stone, not to mention about 4,000 of the scripts.

‘It was the most extensive urban culture of its period,’ said Indus expert Andrew Robinson in a 2015 study published in Nature.

‘[It had] a population of perhaps 1 million and a vigorous maritime export trade to the Gulf and cities such as Ur in Mesopotamia, where objects inscribed with Indus signs have been discovered.’

‘Astonishingly, the culture has left no archaeological evidence of armies or warfare.’

Archaeological discoveries suggest that trade routes between Mesopotamia and the Indus were active during the 3rd millennium BC, leading to the development of Indus-Mesopotamia relations.

Along with the difficulty in deciphering the text, no one yet knows for sure why such a great civilisation vanished around 1300 BC.

One theory, which emerged in 2012, is that climate change led to the collapse – namely, rising temperatures causing fewer monsoons.

The civilization’s enormous success relied fundamentally on monsoons for water and farming, so changes in climate would have been disastrous.

Another theory, which is supported by archaeological evidence, is that the major trigger for the decline was earthquakes.

A 2006 study said: ‘Earthquakes affected the demise of several Harappan sites either by direct shaking damage, altering the water supply, or by changing the relative sea level.’