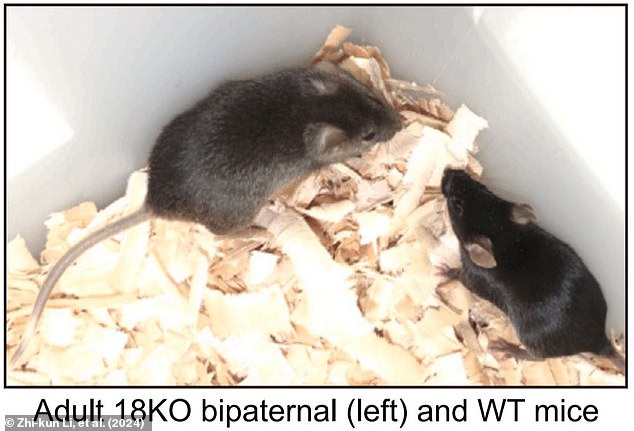

The first mouse with two biological fathers has survived until adulthood, a new study has revealed.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences say they have succeeded in breeding mice using only genetic material from two males.

Through a technique called ’embryonic stem cell engineering’, scientists created eggs from the sperm of one father which could be fertilised by the other.

The stem cell technique used by the researchers is not entirely new, but all previous attempts faced seemingly insurmountable problems.

Mice bred using two sets of male genes either failed to grow at all or were born with severe developmental defects that prevented them from reaching adulthood.

However, by editing 20 different genes in the mice’s stem cells, the researchers were able to prevent these issues.

Co-author of the study Dr Wei Li says: ‘This work will help to address a number of limitations in stem cell and regenerative medicine research.’

While it is currently only possible in mice, this major breakthrough could pave the way for gay men to have children who are biologically related to both fathers.

In order to breed offspring which have two biological fathers, the researchers first needed to transform the male sex cells from one parent into female sex cells.

The scientists took sperm from a mouse and injected it into a type of cell called an oocyte – an immature egg cell that has had its genetic material removed in a process called enucleation.

This created a stem cell – a type of cell with the potential to become any other type of cell in the body – which contained only male DNA from the first parent.

The researchers then took one of these stem cells and a sperm cell from another male and injected both into another enucleated immature egg.

These male cells combined to create an embryonic stem cell containing the DNA of both parents, which was then used to create an embryo which could be implanted in a surrogate mother.

Once the embryo had developed, the mother gave birth to the offspring, which contained only genetic material from the two males.

Scientists have known for a long time that this is possible and have managed to create viable embryos using the technique.

However, no one has previously managed to create ‘bi-paternal’ mice that are actually capable of surviving to adulthood.

During heterosexual reproduction, genetic material from a male carried by the sperm combines with genetic material from a female contained in the egg, or ovum.

When this happens, a group of genes called ‘homologous chromosomes’ from the mother come together with those from the father and combine in a process called ‘crossing over’.

But when both sets of homologous chromosomes come from either two males or two females, the genes don’t copy over properly, leading to ‘imprinting abnormalities’.

These abnormalities can cause developmental defects which prevent the offspring from living healthy lives.

Co-author Dr Qi Zhou says: ‘The unique characteristics of imprinting genes have led scientists to believe that they are a fundamental barrier to unisexual reproduction in mammals.

‘Even when constructing bi-maternal or bi-paternal embryos artificially, they fail to develop properly, and they stall at some point during development due to these genes.’

In this study, the researchers used a gene editing technology called CRISPR to make changes to mice’s DNA in order to prevent imprinting abnormalities.

After creating stem cells from the first male’s sperm, they inserted or removed sections of genetic code at 20 places in the mice’s DNA that control imprinting.

When these genetically modified stem cells were combined with the sperm from another male, they were much more likely to develop properly.

These changes resulted in mice with two fathers who were able to live until adulthood for the first time ever.

Study co-author Dr Guan-Zheng Luo, of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, says: ‘These findings provide strong evidence that imprinting abnormalities are the main barrier to mammalian unisexual reproduction.

‘This approach can significantly improve the developmental outcomes of embryonic stem cells and cloned animals, paving a promising path for the advancement of regenerative medicine.’

The authors do acknowledge some significant limitations to these findings.

Only 11.8 per cent of the viable embryos were capable of developing to birth and not every pup which was born lived to adulthood.

The mice that did live to adulthood showed altered growth, shortened lifespans, and were sterile.

However, these results show the first promising steps towards giving gay men the option to have children who are related to both of their fathers.

In theory, it could be possible to use a similar technique to create an embryo using stem cells derived from one human partner and sperm from the other.

Although the child would still need to be carried to term by a female surrogate, they would have genetic material only from both of their fathers.

Currently, the researchers are planning to try this approach in larger animals like monkeys – and warn that the technological hurdles will be significantly larger.

That means getting the technique to work in humans could require years of effort.

However, not everyone is convinced that scientists should try to pursue this technology in humans, even if it is possible.

Lukasz Konieczka, executive director of the LGBT+ charity Mosaic Trust, told MailOnline: ”I do understand that some might have a strong desire to have biological children as it offers some virtual immortality, as psychologists call it.

‘I do not think it is necessary to spend time and resources on such technology as we still have children who are alive today, stuck in a care system due to neglectful or abusive biological parents.’

Since the technique requires editing the genome of the parent’s stem cells, it is also prohibited in humans.

The International Society for Stem Cell Research’s ethical guidelines for stem cell research do not allow heritable genome editing for reproductive purposes nor the use of human stem cell-derived gametes for reproduction because they are deemed as currently unsafe.