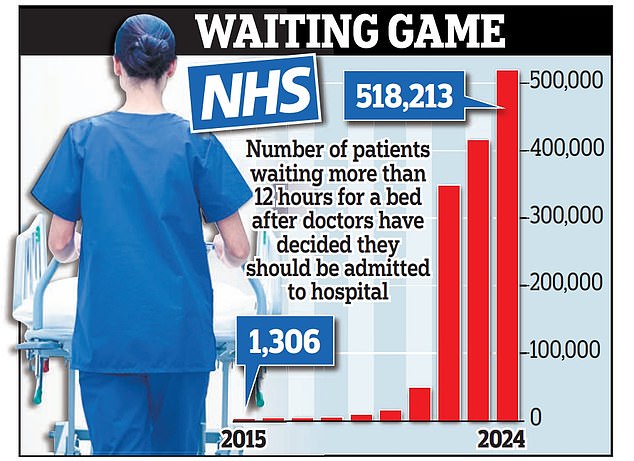

Hospitals left a record 518,000 patients languishing on trolleys in A&E for 12 hours or more last year, damning figures reveal.

The rate is 400 times higher than the 1,306 reported a decade ago and comes amid a major shortage of beds preventing staff moving new arrivals on to wards.

It shows emergency departments were already dangerously overwhelmed before the emergence of this winter’s flu outbreak, forcing around 20 trusts to declare ‘critical incidents’.

NHS England said an average of 5,408 patients a day were in hospital with flu last week, including 256 in critical care.

It believes this number will rise now children have returned to school, where they risk catching the virus and taking it home to families and vulnerable relatives.

Carrie Johnson, wife of former prime minister Boris, revealed over the weekend she spent the first week of 2025 in an NHS hospital suffering from flu and pneumonia.

She said she had been struggling to breathe properly during a ‘nasty’ infection lasting nearly 18 days, and urged the public to get a flu jab.

Figures being published this Thursday are expected to show the NHS is enduring its worst flu season for a decade.

It comes as Labour was last night accused of being ‘asleep at the wheel’ during the crisis, which is expected to deepen this week.

Professor Phil Banfield, chair of the British Medical Association, described corridor care as ‘undignified’ and ‘unsafe’, warning scenes inside NHS hospitals are now ‘akin to those seen in developing countries‘.

He said hundreds of patients are suffering avoidable harm and deaths every week, with some dying before they are even seen by medics.

Some A&Es are running at more than 200 per cent capacity, with waits of up to 50 hours for a bed and ambulances in 18-deep queues outside waiting to hand over new arrivals.

Last week Whittington Hospital in north London published multiple adverts for nurses to work overtime providing ‘corridor care’ to patients on trolleys.

And NHS trusts nationwide are now installing power sockets and oxygen lines in corridors as they prepare to treat more patients in trolleys along their walls.

The Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) said corridors are ‘open, noisy, brightly lit, often cold’, making it ‘difficult if not impossible’ for patients to rest.

It stressed it is ‘not possible’ to control the spread of infection in them, that it is ‘challenging’ for staff to monitor patients, and that privacy, dignity and confidentiality are ‘not maintained.

The RCEM warns long waits in A&E are extremely dangerous and are estimated to have contributed to 14,000 deaths in 2023. Meanwhile A&Es and ambulance services suffered their busiest year ever in 2024 and crews dealt with more incidents in December than any previous month.

There were a record 518,213 waits of 12 hours or more in A&E last year – timed from when doctors made a decision to admit the patient – according to analysis of NHS England data by the Liberal Democrats.

This is up by more than 100,000 – or 25 per cent – on the previous year, when there were 415,136.

In stark contrast, there were just 1,306 such waits across the whole of 2015 – fewer than now occur in a single day.

Helen Morgan, health and social care spokesman for the Lib Dems, urged Health Secretary Wes Streeting to devise an emergency plan to tackle the ‘shocking and dangerous’ A&E waiting times, saying the Government ‘looks to be asleep at the wheel’.

She said it must include an immediate increase in the number of hospital beds to bring occupancy rates down to a safe level, typically considered to be 85 per cent.

The RCEM said it currently stands at 93 per cent, meaning the NHS needs a further 9,471.

An average of 12,591 hospital beds in England were filled each day last week with patients considered medically fit for discharge but unable to leave. Many will have been waiting for a place in a care home or for care to be arranged in their own home.

Dr Tim Cooksley, immediate past president of the Society for Acute Medicine, said elderly patients left on corridors come to increased harm, including ‘delirium, pressure sores and psychological distress’.

He added: ‘Patient confidence in the NHS is rapidly deteriorating and this is well founded.

‘The worsening of the current winter crisis seen in the past week was predictable and inevitable.’

Professor Banfield described the crisis as a ‘national emergency’ and added: ‘There are people, some elderly and vulnerable, waiting in A&E departments far longer than we could ever have imagined a few years ago and this is directly leading to avoidable harm and preventable deaths.

‘If this was still the pandemic, Cobra [convened to handle matters of national emergency] would be mobilised – why is losing the equivalent of an aeroplane-full of patients each month not provoking the same sense of urgency?’

Dr Adrian Boyle, president of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, described the figures as ‘staggering’ and the situation in A&E as ‘stark’.

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesman said: ‘We inherited a broken NHS, and in our first six months we have taken action to protect A&E departments this winter, introducing the new RSV [respiratory syncytial virus] vaccine, delivering more flu vaccines than last year, and ending the strikes so staff are on the front line not the picket line for the first winter in three years.

‘It will take time, but we are working to break out of this cycle of annual winter crises and will publish an urgent care recovery plan shortly.’