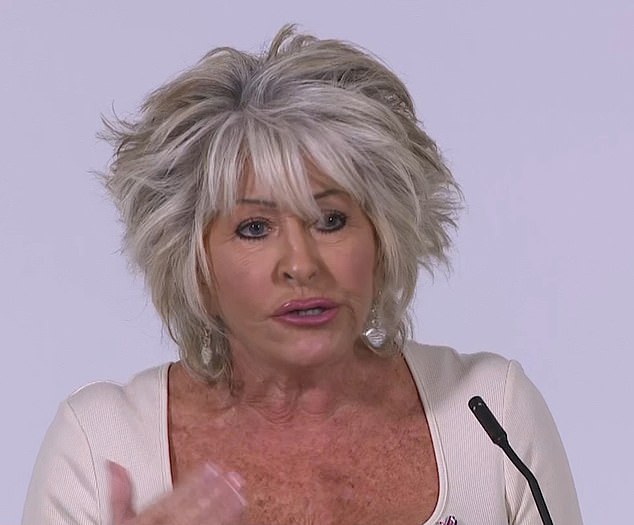

Former police officer Maggie Oliver is angry. Twelve years ago she famously turned whistleblower to expose the horror of young girls being sexually abused by gangs – losing her home and coming close to a breakdown in the process.

But since then, far from getting better, things have got worse. ‘Speaking out cost me so much but I felt a duty to the thousands of children abused by grooming gangs,’ says Maggie, a widowed mother of four.

‘I was appalled by the way politicians and chief constables were deliberately turning a blind eye, so it became a personal crusade for me. I never imagined that these gangs would still be getting away with ruining children’s lives all these years later.’

Maggie reveals how she took on such police apathy in the new series of hit Daily Mail podcast, Everything I Know About Me.

These days, she hears victims’ stories first-hand through her work running her charity the Maggie Oliver Foundation, set up in 2019 to support all survivors of sexual abuse.

From the 13-year-old girl who, for two years, was trafficked to men in northern towns, to the 12-year-old who killed herself after she was raped and blackmailed then ignored by police, Maggie is aware that children are still being horrifically exploited.

‘I’m told by many victims and survivors who come to us for help that the situation is now even worse,’ she says.

Previously, gangs tended to prey on the most vulnerable children in our society – many were in care or from disadvantaged homes – but now no child with internet access is safe. Most secondary school-aged children now have smartphones and social media accounts, so paedophiles can access them anywhere, any time, online.

As a result, Maggie wants to warn every family that as well as keeping tabs on online interactions, they should have open conversations about the risks these gangs pose before children start secondary school.

As for the things to look out for, the first contact may come in the form of a private message on Snapchat, Instagram or another social media app.

Usually it’s from a man who may pay the girl exaggerated compliments, giving the impression they are interested in a loving relationship, before asking her to send photos of an increasingly explicit nature.

Then comes the blackmail – threatening to share images with her family, or even set the family home on fire – before ‘selling’ her on to other abusers. Children soon feel terrified about the consequences of confiding in parents, so Maggie advises making it clear to them that they can always tell us what’s going on in their lives, without fear of being ‘in trouble’.

Making people aware of these most heinous crimes has been Maggie’s motivation ever since she resigned from Greater Manchester Police in 2012. But not everyone was supportive: ‘There were attempts, from the highest ranks within the police force, to discredit me because people didn’t like me drawing attention to it.’

She believes this is partly due to a skewed notion of preventing racial disharmony, because the gang members in Rochdale – and indeed grooming gangs in other northern towns – were predominantly men of Pakistani origin.

But misogyny was surely at play, too: she says young girls trapped in appalling abuse were written off as troublemakers by police.

‘The teenagers targeted by gangs were regarded as leading ‘chaotic lifestyles’ involving drink and drugs, so they were blamed and their experiences were taken even less seriously. Some of these vulnerable children were even referred to as ‘child prostitutes’, for heaven’s sake.’

Add the fact that only two per cent of reported cases of rape or sexual abuse ever make it to court and, she says: ‘It’s as if these crimes, which mostly, though not always, affect women, have become decriminalised.’

Maggie joined the Greater Manchester Police in 1997, aged 41, and moved to the Serious Crimes Division, which investigates murders, rapes and serious sexual assaults, in 2003. She is best known for her role as a detective on the Rochdale case.

Nine men, eight originally from Pakistan and one from Afghanistan, plied girls as young as 12 with alcohol and drugs before ferrying them around the north of England in taxis to be raped by other predators.

They were convicted of charges including trafficking girls for sex, rape and conspiracy to engage in sexual activity with children and, in 2012, given sentences ranging between four and 19 years, which Maggie considered inadequate.

Feeling the children involved had been repeatedly failed, Maggie resigned after the trial in order to publicly blow the whistle, having served 16 years as a police officer.

Speaking up for the victims, and against the powers-that-be who turned a blind eye, Maggie’s profile became so high that she became a regular on Loose Women and in 2018 was a contestant on Celebrity Big Brother. She felt both would help to keep the spotlight on her work.

Now 69, this formidable woman had been motivated to speak out due to the treatment of one girl in particular.

This teenager was given the pseudonym ‘Amber’ when she was portrayed by an actress in Three Girls, the 2017 BAFTA-winning BBC drama about the Rochdale abuse ring, on which Maggie acted as programme consultant.

Amber, abused by the gang from the age of 15, was wrongly accused of recruiting other children into it. She finally received an apology from the Chief Constable in 2022

‘Amber’s abusers were left free to abuse other girls while Amber, who had two children by then, was investigated by social services,’ she says. ‘Despite having no previous concerns, they tried unsuccessfully to take her kids away. This, to a young woman who had already suffered so much at the hands of these men.’ By 2017 all but two of the abusers had been freed.

‘One survivor, still a child, bumped into her rapist in the aisle of a supermarket, while another was horrified to open her door to find the takeaway delivery driver was one of the men who had abused her,’ says Maggie, who still struggles to comprehend how millions of pounds of taxpayers’ money was granted to convicted child rapists to fight against extradition to Pakistan.

‘Many of them argued they had children themselves and were entitled, under human rights laws, to a family life,’ she says. ‘In my view, a man who rapes a 12-year-old child is an animal, whose human rights should never come before those of his victims.’

In a report on the Rochdale scandal released earlier this year, Greater Manchester Police apologised and said cases were handled very differently now.

A GMP spokesperson told us: ‘Our investigations into non-recent CSE [child sexual exploitation] will not go away until offenders are held responsible for their appalling actions.’

And yet still the crimes mount up.

The Mancunian grandmother of three is so overcome with emotion that she has to pause several times while recounting the tragic story of one 12-year-old girl, whose family contacted her charity last year. ‘It’s an ongoing case, so I can’t say much about it,’ says Maggie. ‘But this little girl was groomed online and then raped and blackmailed, with threats to tell her family and school friends. The police were informed but took no action and in the end, she took her own life.’

Then there’s the 11-year-old girl whose father got in touch with the charity in 2021 after checking his daughter’s phone and discovering, on Snapchat, messages from several men who had coerced her into sending ‘inappropriate images’ of herself, and were blackmailing and threatening her.

This 11-year-old girl was, thankfully, rescued.

Others have been less fortunate. The family of one girl who, from the age of 13, was groomed by a man online and then sold for sex to many other men throughout the north of England, turned to The Maggie Oliver Foundation in desperation in 2020, when police failed to act.

Her father reported the child missing at least 56 times but, far from this leading to an investigation, he was himself arrested on one occasion for trying to stop his daughter leaving with her abusers.

As well as horrific sexual abuse, on one occasion her throat was cut, leading, mercifully, only to superficial wounds. On another, her coat hood was set on fire.

When the teenager finally plucked up courage to talk to police, she received death threats and was thrown in a canal by her attackers. ‘The girl is now 19 and feels so totally let down by the system she’s no longer prepared to engage with police,’ says Maggie.

A group of young women from Manchester contacted Maggie’s charity in 2021 alleging they had been raped and exploited by the same gang of adult men since their early teens.

The grooming process had been similar for each of them, with one perpetrator offering ‘loving’ attention before trafficking them throughout the UK and forcing them to have sex with other men.

‘Serious violence was used on each of them,’ says Maggie. ‘One survivor described how she was bitten, burned and beaten during a particularly brutal rape and how she was raped by approximately 150 men from the age of 13.’

Despite producing a significant amount of evidence, including phone messages and photographs of injuries, they were told it did not reach the ‘evidential threshold for prosecution’.

Following publicity generated by Maggie’s foundation, the investigation was reopened. However, three years later, still no charges have been brought.

It is the trauma inflicted on girls that keeps Maggie speaking out about this abuse. She believes grooming gangs operate predominantly in the north of England.

‘Because it’s happening in the north it often doesn’t make national news headlines, which means many people don’t realise it’s still going on,’ says Maggie, her frustration evident. She says the manpower required to investigate these crimes, given the numbers of abusers involved, also creates an unwillingness by police chiefs to commit the resources needed to tackle the problem.

The gangs are usually networks of men, aged from late teens – the ones usually given the job of luring girls in – to late middle age and often live in different towns.

In high-profile cases in Rotherham, Rochdale and Telford, gang members, many of whom were of South Asian-origin, were found to run takeaways, or drive taxis, giving them access to children who were out, unchaperoned, at night.

However, there is ongoing controversy about the typical profile of grooming gangs, with a Home Office-commissioned study of available data in 2020 revealing that group-based child sexual exploitation offenders are most commonly white men under 30.

Previous research from 2015 revealed that, of 1,231 perpetrators of ‘group and gang-based child sexual exploitation’, 42 per cent were white, 14 per cent were defined as Asian or Asian British and 17 per cent were black.

Technology, while making victims easier targets, has also made it harder to track down perpetrators. Those who might once have been identifiable from car registrations, or the location where grooming began, can now hide behind IP addresses registered abroad.

Maggie explains: ‘These investigations can take years, so if police can discredit the victims in some way, usually by claiming they have perverted the course of justice or told ‘lies’, they can justify dropping the case on the grounds that the Crown Prosecution Service won’t be able to prove ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ that their abusers are guilty. The only way that is going to change is with greater police resourcing and better understanding.’

Maggie, disillusioned after contributing evidence to public reviews into child grooming which, she says, ‘only lead to recommendations, not obligations’, isn’t holding out much hope.

Last year, she was invited to meet Rishi Sunak and Suella Braverman, then Prime Minister and Home Secretary, on their visit to Rochdale where a new strategy was announced to tackle organised child sexual abuse.

The multi-pronged approach was to include setting up a new task force, supported by the National Crime Agency and specialist officers.

Additionally, anyone working with children would have a duty to report suspicions of abuse, while a helpline for whistleblowers was to be set up and laws updated so that being part of a grooming gang would be considered an aggravating factor in sentencing.

‘It sounded great but we haven’t actually seen any change in the way things are dealt with,’ says Maggie.

It’s clear, however, that while she has breath in her body, Maggie will keep speaking out about grooming gangs, as well as other sexual abuses suffered by the 4,500 survivors her charity has supported since 2019.

She admits: ‘It’s been hard on my kids – they only have one living parent, and I was in a high state of stress for years. Then, after I resigned, I couldn’t eat or sleep and became very depressed.

‘But one of the reasons I decided to speak out is because I couldn’t bear for my children to learn, in the future, about what had been going on, and wonder why their mum had stayed quiet. They are proud of me for doing my best to put something right that was very wrong.’

Countless young survivors will also be forever grateful to Maggie for that.

All episodes of Everything I Know About Me with Maggie Oliver are available now. Listen wherever you get your podcasts.