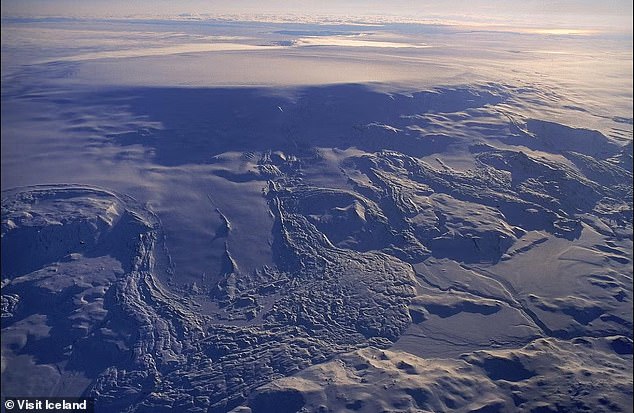

One of Iceland’s largest volcanoes is on the brink of erupting, experts have warned.

Bárðarbunga – the second-largest volcano in the country – has been hit with a swarm of 130 earthquakes within just five hours.

This is a key sign an eruption could be imminent, according to The Icelandic Meteorological Office (IMO).

As a precaution, the aviation colour-code for Bárðarbunga has been raised from green to yellow, indicating ‘heightened activity above normal background levels’.

Aviation colour-codes give pilots and aviation authorities information about the potential presence of volcanic ash in the atmosphere, which could impair flights.

Bárðarbunga – located under Iceland’s largest ice cap (Vatnajökull) in the centre of the country – last erupted a decade ago, prompting a red travel alert.

The volcano’s previous eruption in 2014/15 emitted large volumes of sulphur dioxide and impacted air quality.

However, there was little effect on flights outside of the immediate vicinity as it didn’t produce as much volcanic ash.

‘Bárðarbunga is unique in that it is an unusually large volcanic system, partly covered by a glacier,’ said the IMO in a statement.

‘The observed seismicity is consistent with increased pressure caused by magma accumulation, which has been ongoing since the last eruption in 2015.’

Fears started on Tuesday when a ‘strong’ earthquake swarm began shortly after 6am UTC in the northwestern part of the Bárðarbunga caldera, according to IMO.

Earthquake activity was most intense until around 9am UTC, after which it began to decrease, although earthquakes are still being recorded in the area, it said.

The largest quake at 8:05 UTC registered at magnitude 5.1, capable of ‘minor damage’, while 17 earthquakes measured magnitude 3 or higher.

Earthquake activity has been increasing gradually in Bárðarbunga over recent months and four earthquakes measuring magnitude 5 or higher were detected in 2024, the department added.

In the past four years, the Icelandic volcanoes of Fagradalsfjall and Sundhnúkur have hit the headlines for consistent eruptions, although these are further southwest, closer to capital city Reykjavík.

Many of these eruptions were preceded by earthquakes with magnitudes somewhere between five and six.

However, unlike recent eruptions in the Reykjanes Peninsula, Bárðarbunga is located in a more remote area, within Iceland’s largest ice cap, meaning people and infrastructure are less at risk.

Earthquakes can trigger volcanic eruptions through severe movement of tectonic plates – the jigsaw-style sections of Earth’s crust and uppermost mantle.

Valentin Troll, professor of petrology and geochemistry at Uppsala University in Sweden, thinks the swarms could potentially lead to an eruption.

‘The unrest at Bárðarbunga is in addition to long term inflation of the system over the last few years and could herald developments towards a new eruption,’ he told MailOnline.

‘However, earthquake swarms like the recent one are not necessarily leading to an eruption, and it is thus too early to be certain.

‘If an eruption occurs, it would possibly look like a repeat of the 2024/15 eruption, which was spectacular to watch but posed no serious danger to populations or livestock and infrastructure due its relative remoteness.

‘Alternatively, we may face an eruption inside the caldera (under the ice), which could lead to unpleasant phreatomagmatic eruptions where magma/lava and glacial melt water interact to cause steam explosions.’

Dr Philip Collins, deputy dean at Brunel University London’s department of civil and environmental engineering, said the new earthquakes ‘reflect the movement of magma at depth’.

‘At the moment, there’s no indication that big eruption will happen, but volcanoes can be difficult to predict,’ Dr Collins told MailOnline.

‘[The magma] may be forcing its way into new areas and causing fracturing of the rock at depth, but whether there is enough volume or pressure for this to reach the surface isn’t clear yet.

‘If an eruption did occur, the first sign might be increased meltwater from the glacier that sits over much of the volcanic area.’

Large earthquakes – greater than magnitude 6 – can trigger an eruption or to some type of unrest at a nearby volcano, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Volcanoes can only be triggered into eruption by nearby tectonic earthquakes if they are already poised to erupt – when there’s enough ‘eruptible’ magma within the volcanic system and significant pressure within the magma storage region.

‘If those conditions exist, it’s possible that large tectonic earthquakes might cause dissolved gases to come out of the magma (like a shaken soda bottle), increasing the pressure and possibly leading to an eruption,’ USGS says.

In the past four years, Iceland has seen a series of eruptions at the Reykjanes Peninsula, a volcanic hotspot southwest of capital Reykjavik.

After remaining dormant for 800 years, the Reykjanes Peninsula suddenly became active again in 2021 at the Fagradalsfjall volcano.

In late 2023 and early 2024, new volcanic fissures formed near the fishing town of Grindavik, pumping huge plumes of lava out onto the surface.

The resulting eruptions led to the evacuation of the town, destroyed houses and repeatedly closed the Blue Lagoon – one of the country’s most popular tourist destinations.

In November 2024, the geothermal spa closed when its car park was engulfed in lava, although the Blue Lagoon website says ‘specialized protective barriers’ are ‘safeguarding Blue Lagoon’s vital infrastructure against potential lava flows’.

For many locals, the events have revived the trauma of the disastrous explosion at another of Iceland’s volcanoes, Eyjafjallajokull, back in 2010.

While the eruption didn’t kill anyone, it did produce a huge cloud of ash that prompted the biggest global aviation shutdown since World War II.