Most bridegrooms keep their wedding speech safely in the inside pocket of their suit. Will Sebag-Montefiore kept a small bottle of Tabasco Habanero Sauce, a very spicy version of an already spicy condiment. ‘Regular Tabasco doesn’t cut the mustard – I had to have their hottest one. I guess it is a full-on addiction,’ says the comedian and actor, 33. ‘I have hot sauce with every meal.’ Yes, even on his wedding day.

He is not the only one. Hot sauce has become, well, very hot. In the UK there are thousands of consumers admitting to slathering it on pretty much every dish they consume, from eggs at breakfast to ice cream before bed. There is also a growing army of companies – from multinational food giants to tiny small-batch sauce makers – that supply this craving.

In short, Britain has gone mad for hot sauce, a term used to describe any condiment using chillies as the key ingredient, from Nando’s mild peri-peri sauce to Wiltshire Chilli Farm’s Regret, which contains a dash of chilli extract that is six times hotter than pepper spray. Iceland is about to launch Pepper X Chicken Tikka Masala and Pepper X Chilli Mac & Cheese: ready meals made from the world’s hottest pepper. Owing to the intense level of spice, the supermarket has even introduced a purchasing restriction, requiring customers to be 18 or older.

Industry bigwigs talk it up as a ‘ketchup killer’. At online supermarket Ocado the sales of hot sauces in 2024 are up 24.5 per cent on 2019, compared with a mere two per cent increase in mustard sales. Ocado’s Meri La Bella, says: ‘We think there is huge growth potential still in the hot sauce category and predict this momentum will continue.’

That’s partly because of all the new kids on the block. Back in 2019, Ocado stocked 63 hot sauces. It now sells 99 – way more than the 51 ketchups and 50 mustards it stocks. Mintel, a market research company, calculates that a decade ago, hot sauces made up one-third of total UK table sauce launches, a category that includes ketchup, mustard and the like. This year, it is nearly half (48 per cent).

The boom is not dissimilar to the gin craze of a decade ago – very low start-up costs and some clever branding mean you can have your concept on shop shelves remarkably quickly. Euromonitor, a market-research firm, reckons the global hot sauce market is now worth £4.6 billion.

The market has attracted quite a few celebrities, notably singer Ed Sheeran, who has teamed up with Heinz to make Tingly Ted’s. Jeremy Clarkson has created a range, OX7 Sauces, named after the postcode of his Diddly Squat Farm in Oxfordshire. England footballer Bukayo Saka has a collaboration with Nando’s called Peri-Peri Saka and Allan Lamb, the former England cricketer, has Banhoek Chilli Oil, a staple in my store cupboard not just because he was a boyhood hero of mine but also because it goes so well on pizza.

One of the newest arrivals, launched in October, is Cloud 23. It is the creation of Brooklyn Beckham, 25, the eldest son of David and Victoria. He is trying to make his name as an online cook and ‘tastemaker’. So why choose a hot sauce rather than, say, a whisky, a cheese or a salad dressing? All have attracted celebrity branding. ‘Three and a half years ago I was sitting in my house with my wife, trying to figure out what I wanted to do,’ he tells me by phone from California. ‘I found out how to make hot sauce, and I gave it a crack, creating the original Cloud 23 recipe.’

That is another reason why hot sauce brands have mushroomed in recent years: it is relatively easy to make. Most recipes are, in simple terms, chillies, vinegar, salt and some sugar put into a saucepan and boiled – although, as Beckham says, ‘If you’ve never made hot sauce before, make sure you open a window – we were coughing all night because I forgot to.’

That’s the effect of capsaicin, a neurotoxin found in chilli peppers, being released into the kitchen air, as it can catch in the back of your throat and make you cry. While many people hate the effects, some love the tingle and buzz they get from a slather of hot sauce. ‘Physiologically it is an endorphin release, which is what gets people hooked on it,’ explains Liam Kerr, 30. He is the founder of Heriot Hott Sauce, an Edinburgh-based company he launched in lockdown while studying for a master’s in marine biology. ‘That’s why people go back for hotter and hotter sauces,’ he says. ‘They start with a mild sauce, but then your body goes, “That’s not enough”, because you get accustomed to it. So you need something hotter for your next rush.’

Initially, Kerr’s spiciest sauce was something called Super Hot Sriracha but, ‘People in food markets were saying it wasn’t hot enough, so we then made Sriracha X where we added dried carolina reapers [super-hot chillies] – the burn is way longer.’

The other big driver is young people: Gen Zs and millennials are enthralled by the hunt for heat. ‘What got me addicted was the Nando’s barometer,’ says one Gen Z, 24, who spends £50 a month on hot sauce. ‘When you first went there with your friends at 14, you needed to be able to have medium just to be cool [lemon & herb being for lightweights]. But then that stopped being enough, so you had to go for hot. And then hotter – just to keep up. I think my tastebuds became warped.’

The zeitgeist is certainly spicy. Hot Ones, a hugely popular US programme broadcast on YouTube (its most popular episode has garnered more than 120 million views), sees celebrities interviewed while eating chicken wings doused in progressively spicier sauces. Jennifer Lawrence, Paul Mescal, Gordon Ramsay, Florence Pugh and Idris Elba have all sweated their way through the challenge.

Beckham junior is a big fan. ‘Me and my wife are obsessed with Hot Ones. When we have date nights at home, sometimes I cook chicken wings, get a bunch of different hot sauces and we try to re-create the show.’

The spiciness of chillies is usually measured using the Scoville scale. A standard jalapeño red chilli from Tesco is between 2,000 and 8,000; a scotch bonnet (a squashed round chilli you can often find in specialist shops) is between 100,000 and 350,000; a carolina reaper, the hottest chilli widely grown, can be up to 2.3 million.

An increasing number of hot sauces include plenty of scotch bonnets and even some carolina reapers to appeal to the unashamedly macho market, which explains sauces available with names such as Regret, Hulk Juice, Holy F**k, Beyond Insanity and Zombie Apocalypse.

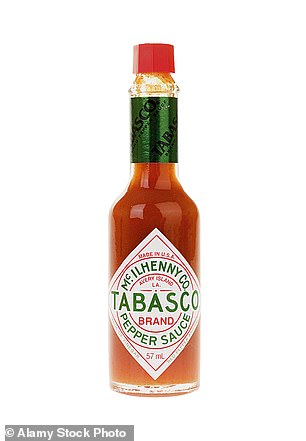

The phenomenal success of hot sauce in Britain is, in many ways, a story of how we have always been a trading nation, open to cuisines and cultures from overseas. Tabasco, the first commercial hot sauce, was invented in Louisiana in 1868 – a simple blend of peppers, salt and vinegar. For many Brits of my generation, growing up in the 1970s, this was the only hot sauce they had in their cupboard – used sparingly in a bloody mary cocktail. Then the generation of West Indian people settling after the war helped popularise Caribbean hot sauce, a version often including fruit, such as mango, alongside scotch bonnet chillies to balance the heat.

By the early 2000s, British holidaymakers who had fallen in love with Thailand had discovered sriracha, a type of Thai hot sauce that is fermented, the most famous brand being Flying Goose, with its distinctive green top. Fermentation gives the sauce a natural acidity, preserving its shelf life without imparting a sourness that can make vinegar-based hot sauces a bit sharp.

In recent years, Korean hot sauces, made using gochujang, a punchy fermented chilli paste, have also taken off, alongside the rise of Korean fried chicken. ‘Korean food has become so much more popular in the past ten years in the UK, Ireland and Europe,’ says Sofie Rooney, 34, a former branding and marketing executive who co-founded Chimac in Dublin during lockdown.

‘There are all these different influences, such as K-pop, Korean beauty, Korean television such as Squid Game…’ Chimac makes Korean-style hot sauces in stylish bottles. ‘Traditionally, Irish and English fare is comforting, but it’s not spicy at all,’ says Rooney. ‘It’s a reflection of how much we travel now, and how we get to try different cultures and cuisines from everywhere.’ Rooney’s Sriracha Caramel, a sweet, sticky nectar, is designed for savoury dishes, but some people are ‘so addicted to their hot sauce, they have it with desserts’. Beckham agrees, saying that he eats vanilla ice cream with a tablespoon of his own hot sauce. ‘Honestly, I’m not even joking – just try it. It works so well.’

Ireland has produced quite a number of hot sauce brands, notably White Mausu, which has gained a cult audience, myself included, who can’t get enough of its peanut rayu: a Japanese-style chilli and nut combination. I’ve been known to eat it straight out of the jar.

The real appeal of these spicy condiments, however, is simple. A good hot sauce or chilli oil ‘can turn plain, boring food into something exciting and tasty in an instant’, says Jasper O’Connor, co-founder of White Mausu. A plate of vegetables, some fried eggs on toast or a bowl of leftover potatoes… all become both exotic and gourmet. As O’Connor puts it: ‘Your two-minute lunch all of a sudden becomes something special.’

How I fell for hot sauce

By Tom Parker Bowles

You never forget your first time. For me, it started with a drop of Tabasco from an old bottle that was kept not in the kitchen cupboard, rather on the drinks table in the drawing room at home.

‘Go on, lick it,’ dared my sister as I eyed the angry red splodge on the back of my hand. I screwed up my eyes, stuck out my tongue and plunged headfirst into a whole new world of pleasure and pain.

It was like nothing I’d experienced before: a hit of vinegar then heat, transforming into raging fire, great waves of the stuff, tearing across my tastebuds like flames through bone-dry bush. My eyes began to water, my mouth began to throb. For a moment I couldn’t speak, as the inferno surged down my throat. ‘Are you OK? asked my sister, fear etched on her face. If I dropped dead, our afternoon trip to the video shop was a goner.

She plied me with water but this just made things worse. Now my throat was aflame and I had to sit down, splutter and pant frantically. But when the inferno died down, I suddenly felt unbelievably alive, my senses pin-sharp, my brain flooded with delight. It was like that moment in The Wizard of Oz where dull sepia is transformed into dazzling Technicolor. My life would never be the same again.

From there, with Tabasco as my gateway drug, I quickly moved to the curry house: first madras, then vindaloo. Before long I was slurping El Yucateco Habanero Salsa Picante, subscribing to Chile Pepper magazine and descending into the dark, diabolical world of ‘extract sauces’: the masochistic likes of Dave’s Insanity; sauces up to 1,000 times hotter than Tabasco.

Not only did I start to collect sauces from across the globe, I even made a pilgrimage to the National Fiery Foods & BBQ Show in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where, in a fit of idiotic, wannabe pungency prowess, I tried a sauce so extreme that it almost knocked me out. Those days are long past, and my urges rather less extreme. But my love for hot sauce still runs fiery through my veins.

For this is no mere condiment – rather, the greatest sauce on earth.