It’s time to rewrite the history textbooks, as a distant new member of our ancestral family tree has been discovered.

Scientists say a new, never-before seen species of human ancestor roamed the Earth as recently as one million years ago.

Called Paranthropus capensis, it was a more slender member of the Paranthropus genus – a close relative of modern humans (homo sapiens).

Paranthropus have previously been dubbed the ‘nutcracker men’ because of their extremely big jaws, robust skull bones and large molar teeth.

They walked on two legs, but had smaller brains than other extinct hominins – which may have contributed to their extinction.

Although not a direct ancestor, we share distant relatives with Paranthropus, which lived in Africa between about one million and 2.7 million years ago.

It’s thought Paranthropus lived in wet grasslands or woodlands, eating plants such as tree fruits and leaves, and possibly small amounts of meat.

Scientists say its discovery could rewrite the entire history of our evolution.

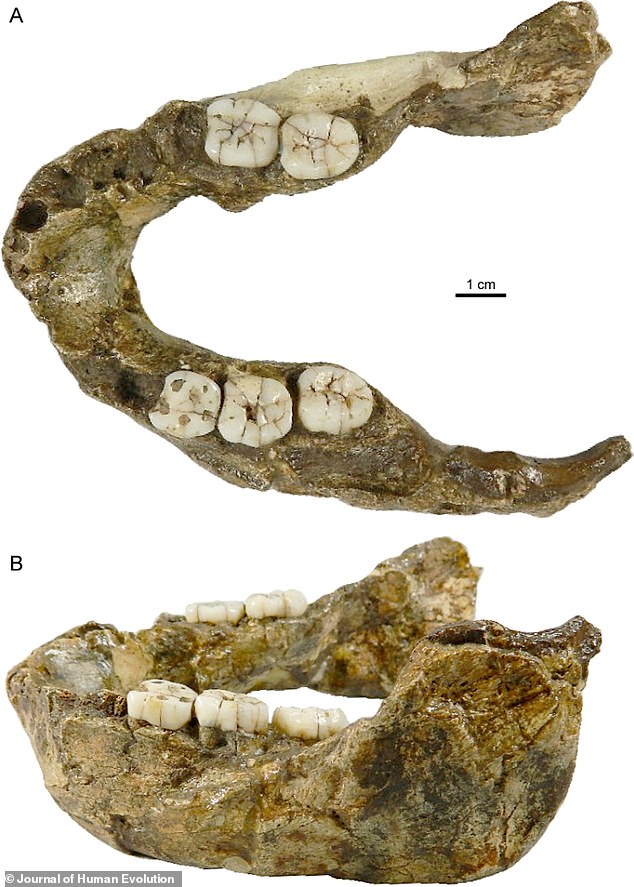

For their study, the researchers examined SK 15, a mandible (lower jaw) discovered in Swartkrans cave, South Africa, back in April 1949.

Located about 20 miles from Johannesburg, the limestone cave is rich in hominin remains including Homo ergaster (a variety of Homo erectus) and Homo habilis.

Initially, SK 15 was dated to around 1.4 million years ago and thought to belong to Homo ergaster, which was the first of our ancestors to look more like modern humans.

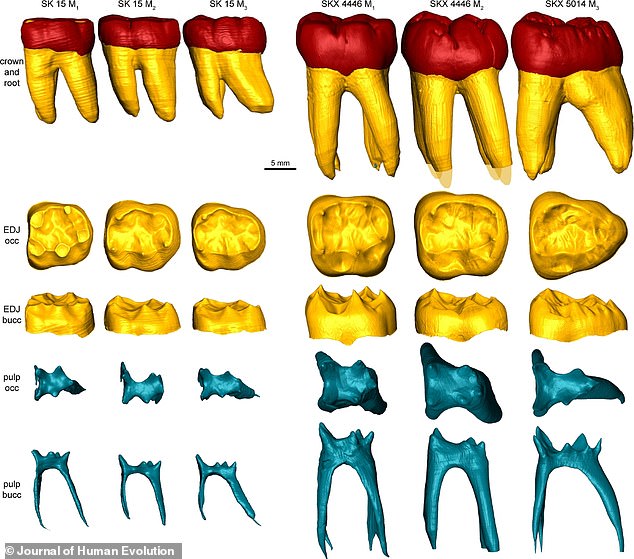

But the new analysis, which involved taking digital 3D scans of the skeletal remains, suggests it belonged to Paranthropus or ‘nutcracker man’, which likely coexisted with other hominins.

The team found the thick, bony part of the mandible that anchors the teeth (‘mandibular corpus’) is proportionally lower and thicker than any known Homo species.

Meanwhile, the molars – the teeth at the very back of the mouth used for grinding food – are more rectangular than Homo molars.

But the jawbone and teeth are slightly smaller than other Paranthropus specimens, leading the team to describe this as a new species – Paranthropus capensis.

‘Paranthropus capensis [was] a more gracile species of Paranthropus than the other three currently recognized species of this genus,’ ay the authors in their paper, published in Journal of Human Evolution.

‘It is most compatible with the morphology of Paranthropus, albeit showing smaller dimensions.’

This is the first time since the 1970s that a new species of Paranthropus has been identified, lead author Clément Zanolli, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Bordeaux, told Live Science.

P. capensis likely lived in Africa 1.4 million years ago alongside P. robustus, but the latter likely had a highly specialized diet, as suggested by bigger jaw and teeth.

‘P. capensis, which displays smaller teeth and a less robust mandible, might have had a more varied diet and potentially exploited different food resources,’ he said.

For more than 60 years it was thought Paranthropus evolved massive back teeth to consume hard food items, although a 2021 study challenged this.

Humans today (homo sapiens) did not evolve from Paranthropus, which reached an evolutionary ‘dead end’ when they died out about 1 million years ago.

But both Homo and Paranthropus are thought to have descended from a group of hominins known as Australopithecus, from which they evolved at least three million years ago.

The reason for the extinction of Paranthropus could be widely debated, but one theory is that their diet was too specialised to adapt to Africa’s changing climate.

Alternatively, they may have lost the battle with early Homo species because their brains weren’t as big.

The fact that P. capensis had more diminutive features than other Paranthropus relatives hints at a further weakness which may have allowed Homo to thrive.

It’s worth bearing in mind that we only have a P. capensis jawbone to go by at the moment – although there could be further fragments from the rest of the body that could reveal more about this species.

What’s more, the new results could help identify other members of the Paranthropus genus, which was first identified by Scottish paleontologist Robert Broom in 1938 with the discovery of P. robustus.

‘SK 15 represents another species of Paranthropus that was previously unrecognized,’ the authors conclude in their paper.

‘Species diversity of Paranthropus in southern Africa deserves to be investigated further.’