NASA has spotted mysterious ‘spiderwebs’ on a never-before-explored region near the equator of Mars.

The agency’s Curiosity rover has been dispatched to probe these bizarre structures — which cover a six to 12 mile stretch of Martian desert — as the machine searches for signs that this long desolate world once supported alien life.

Geologists suspect that the spiderwebs are a gigantic version of a type of crystalized minerals, known as a ‘boxwork,’ that appear inside some caves on Earth.

Some of America’s most spiderweb-like boxwork can be seen on the ceiling of Wind Cave in North Dakota. Its web-like shapes are created as calcium carbonate mineral water seeps into cracks between softer rocks, hardens into crystals, and remains as webbed latticework as those other rocks erode over time.

But the sprawling, over 3,800-acre wide boxwork on Mars differs in that it was likely formed by Martian seawater and may have trapped fossils of ancient life in its web.

‘These ridges will include minerals that crystallized underground, where it would have been warmer,’ according to Rice University geologist Dr Kirsten Siebach.

‘Early Earth microbes could have survived in a similar environment,’ Dr Siebach explained — making the ‘salty liquid water’ that created these Martian webs an ideal location to find lingering fossil evidence of ancient alien microbes.

The discovery comes as Australian researchers have found that a Martian meteorite, which crashed into Northwest Africa, provides more evidence of hot water on Mars.

A chemical analysis of that meteorite suggests conditions were ripe for aquatic life to develop on Earth’s nearest neighbor over four billion years ago.

Ever since it first parachuted down to the Martian surface on August 6, 2012, Curiosity has been exploring the Red Planet for signs of life — as well as hunting for clues about Mars’ climate, geology and where all its ancient water went.

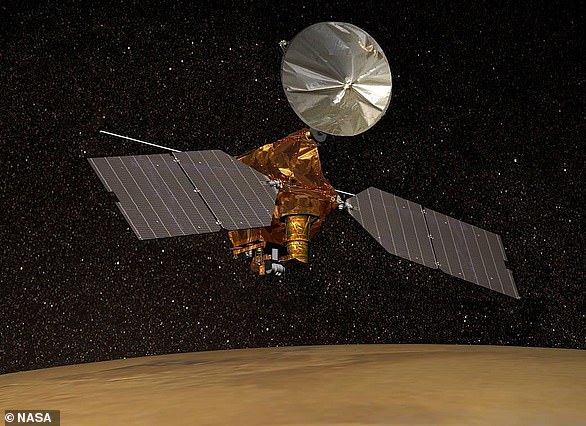

But NASA researchers have been intrigued by the massive geological spiderweb for even longer, ever since their Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter satellite first captured aerial images of this haunting landscape back on December 10, 2006.

How such formations could appear on Mars’ surface is still a mystery, but theories point to the climate chaos that stripped Mars of its water billions of years ago.

The likelihood that evidence of aquatic microbial life of Mars might be caught in this giant web as fossils ‘makes this an exciting place to explore,’ Dr Siebach noted.

This web of potential dead alien microbes and bugs rests in the shadow of a three-mile tall mountain, officially known as ‘Aeolis Mon,’ but nicknamed ‘Mount Sharp.’

Past explorations by the Curiosity rover have revealed many sedimentary layers along the cliff faces of Mount Sharp, suggesting in rich detail that it had been formed by water erosion via ancient lake deposits.

NASA scientists suspect that this erosion helped form the giant crystal spiderweb, as mineral-rich pulses of water seeped and cascaded down Mount Sharp into fractures in the surface rock and then crystallized.

According to satellite mapping work that Dr Siebach published in 2014, at least 113.6 billion gallons of salty, warm mineral-laden water would have been required to create the vast field of crystal webbing, which is bigger than Los Angles Airport (LAX).

‘This is a significant amount of groundwater that must have been present,’ she and her co-author wrote in their paper for the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

‘Mineralization,’ the kind of crystal formation that likely occurred here, ‘is known on Earth to help facilitate preservation of once-habitable environments,’ they noted.

And in Australia this month, scientists working with Martian meteor NWA 7034, discovered after it crashed into Northwest Africa, have found still further evidence that ancient warm oceans on Mars could have easily supported alien life.

‘We used nano-scale geochemistry to detect elemental evidence of hot water on Mars 4.45 billion years ago,’ planetary scientist Dr Aaron Cavosie said in a statement.

‘Geochemical markers of water’ were discovered on meteor NWA 7034, Dr Cavosie explained, based both on the shape of its rocky grain patterns and its chemical composition: ‘tell-tale signs of water-rich fluids from when the grain formed.’

It’s believed that NWA 7034 was ejected from an asteroid impact on Mars that created a crater in the northeast of the ‘Terra Cimmeria-Sirenum’ province in the southern hemisphere of Mars.

A special technique used to date the age of incredibly old zircon minerals via trace amounts of radioactive material, called ‘Uranium–lead dating,’ found that this meteor was made up of some of the oldest Martian volcanic rock ever obtained.

‘The team identified element patterns in this unique zircon, including iron, aluminum, yttrium and sodium,’ Dr Cavosie said, ‘Through nano-scale imaging and spectroscopy.’

‘These elements were added as the zircon formed 4.45 billion years ago,’ he continued, ‘suggesting water was present during early Martian magmatic activity.’

This mixture of hot and mineral-rich water, not unlike the hydrothermal vents that support life deep in Earth’s oceans, point towards the possibility that life was developing on Mars billions of years ago, amid all this volcanic activity.

‘Hydrothermal systems were essential for the development of life on Earth,’ Dr Cavosie explained, ‘and our findings suggest Mars also had water, a key ingredient for habitable environments, during the earliest history of crust formation.’

The Australian planetary scientist and his team at Curtin University in Australia published their results in the journal Science Advances this past Friday.

In its decade-plus on the Red Planet, NASA’s Curiosity rover has trekked roughly 20 miles of the Martian surface for clues about the life that may have once thrived there.

Curiosity will begin studying the spiderweb ridges up close in 2025, according to NASA administrator Bill Nelson, where it will stay for a ‘monthlong journey through Mars’ boxwork.’