The judge who handed custody of Sara Sharif to her father before he beat the 10-year-old to death can today be named in a landmark victory for open justice.

Last month a High Court judge sparked outrage after ordering that none of the professionals involved in the appalling case of the 10-year-old murdered by her father and stepmother could be named because the media cannot be ‘trusted to report fairly.’

It was the first time in British legal history that a judge had been granted anonymity.

The Court of Appeal overturned the gagging order after the Daily Mail and other media organisations argued that judges are the ‘face of justice itself’, they make ‘life-and-death decisions’ and keeping their names secret would have a ‘corrosive impact’ on public confidence in the judicial system

Now it can be revealed that the judge at the centre of Sara’s case is a renowned lawyer who has championed the right of judges to be able to work from home, including for court hearings, because she believes commuting is a ‘complete waste of time’.

Judge Alison Raeside was the first sitting judge in the UK to take maternity leave.

The 66-year-old is married to a fellow circuit judge and has four children, all of whom have entered the legal profession.

In a revealing ‘Women Who Work’ podcast (in Nov 2023), she spoke about the need for judges to have the flexibility to work from home and offered tips on how to be a ‘submarine parent’, providing an insight into her own parenting style.

Judge Raeside did not apply for the anonymity order and neither did the local authority.

The order was imposed by Mr Justice Williams despite no applications to the court to consider anonymity.

Called to the Bar in 1982, Judge Raeside has served as a district judge since 2000 and was appointed as the designated family court judge for Surrey in 2019, serving until 2024 when she was appointed as the Lady Chief Justice’s nominated representative on the HMCTS Board.

Within months of taking on the role at Guildford Family Court, the judge had to take a five-year restraining order out against a father who branded her a ‘vile monster’ in a series of threatening messages during a nine-month online stalking campaign.

Nyron Warmington, 42, was jailed for a year in 2019 after he targeted Judge Raeside because she had barred him from contacting his daughters during family court proceedings.

Using the pseudonym ‘Equality for Fathers’, Warmington posted on Instagram and Facebook about ‘monsters working in the UK courts’.

Just three months after the stalking case, Judge Raeside was asked to consider whether to hand custody of Sara Sharif to her father in October 2019.

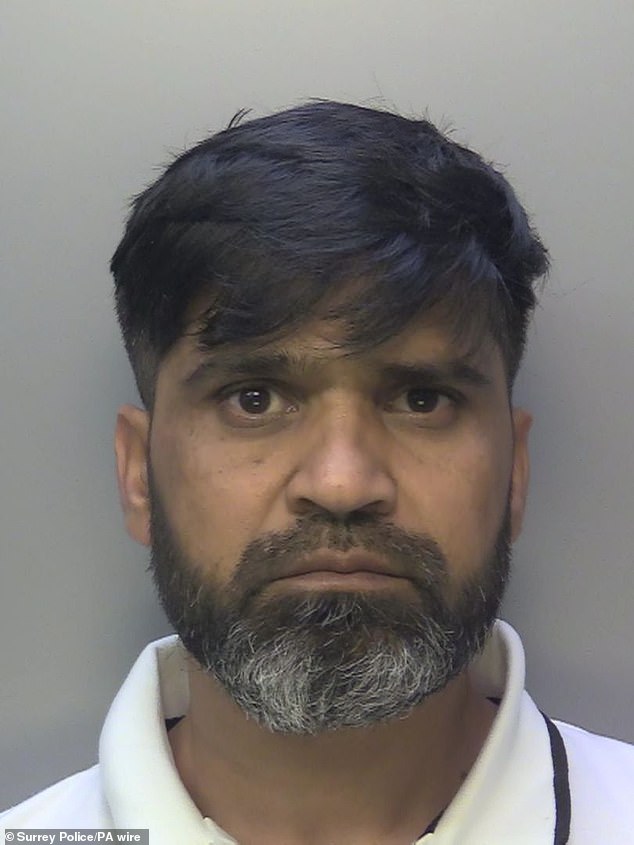

Urfan Sharif, 42, had previously been accused of violence against three ex-partners and two children, including his own, who were burned, bitten and bruised in a catalogue of cruelty dating back 16 years.

Yet police failed to bring charges and social workers later advised that Sara should be placed in his care after he successfully managed to dodge blame.

Court documents reveal how Judge Raeside was hoodwinked by Sharif and his wife Beinash Batool, 30, into blaming Sara’s mother Olga Domin for the abuse.

The judge even praised Batool for taking on Sara and her siblings, saying it was a ‘it is a big ask, it’s amazing to be frank’.

She recommended Ms Domin get help for ‘anger management’, adding: ‘It would be good if you could at least be courteous to her (Batool), be polite to her, be slightly grateful even to her….It’s only thanks to Ms Batool that you’re able to really see them.’

The judge ordered that Sara should live with Sharif as long as Batool supervised Sara’s fortnightly visits with Ms Domin.

She told the two women to shake hands: ‘Maybe you could see if you could shake hands, say hello and see if things could go forward a bit differently.’

Social workers claimed Sara had ‘a really good relationship’ with her stepmother, which was ‘a point of safety’ for her.

It was a mistaken belief that would prove fatal in the schoolgirl’s case, with her father starting to dole out daily beatings within weeks of gaining custody.

Sara suffered an unimaginable ordeal at the hands of her father and stepmother, who bound her arms and legs and hooded her in a plastic bag secured with parcel tape around her head while they battered her with a cricket bat, metal pole and a rolling pin, strangled her until her neck broke, burnt her with an iron and bit her.

When police found her broken little body dumped under the pink covers of her bunk bed by her fleeing family last August, she had suffered more than 100 injuries before her death.

Following their murder conviction in December, High Court judge Mr Justice Williams banned the naming of Judge Raeside and other professionals in the case saying: ‘Seeking to argue that individual social workers or guardians or judges should be held accountable is equivalent to holding the lookout on the Titanic responsible for its sinking rather than the decision making of Captain Smith and the owners of the White Star Line, or blaming the soldiers who went over the top in the Somme on 1 July 1916 for the failure of the offensive rather than the decision making of the generals who drew up the plans.’

But in a significant victory for open justice and media freedom, Sir Geoffrey Vos said: ‘In the circumstances of this case, the judge had no jurisdiction to anonymise the historic judges either on 9 December 2024 or thereafter.

‘He was wrong to do so.’

Sir Geoffrey Vos who oversaw the appeal alongside Lady Justice King and Lord Justice Warby, criticised the ‘procedural irregularity and unfairness’ of Mr Justice Williams’ ruling adding that ‘the judge lost sight of the importance of press scrutiny to the integrity of the justice system.’

The court of Appeal ordered that Judge Raeside can be named today along with two other retired judges who took a limited part at an earlier stage in the proceedings, Judge Sally Williams and Judge Peter Joseph Nathan.

The Court of Appeal judgment said: ‘At the conclusion of the care proceedings, the children were placed with the mother (Olga Sharif) under a child arrangements order.

‘The children eventually returned to live with the father and the step-mother in 2019 with no involvement from the court.

‘The mother and father then jointly applied to the court to have the existing child arrangements order varied by consent, with the support of the social workers’ team.

‘[Raeside J’] was not prepared to approve the variation of the child arrangements order on that basis, and ordered a full report to be prepared by Surrey Social Services.

‘That report concluded that the children were being given stability and appropriate guidance by the father and step-mother and recommended that a child arrangements order should be made in the father’s favour.

‘Having considered the evidence, the report and with the consents of the parties, that order was made in late 2019.

‘It is not for this court to evaluate the course of the historic proceedings. But it should be noted that the historic judges had, as in all cases of this type, the difficult task of assessing the risk of future harm which could only be done against the background of the evidence before them.’