If you are a Sudoku ace or a cryptic crossword champ, you might feel like there is no puzzle you couldn’t crack.

But there are some hidden messages which have baffled even the brainiest code breakers.

Despite massive advances in cryptographic techniques, six codes have stubbornly held onto their secrets for hundreds and sometimes thousands of years.

From the ancient Phaistos Disk to the CIA’s own Kryptos challenge, generations of experts have tried and failed to unlock the mysteries of these lost letters.

However, there is more than just intellectual curiosity on the line.

Cracking the morbid code of the Tamam Shud Case could help police solve a decades-old unsolved murder.

Meanwhile, tackling the mystery of the enigmatic Beale Papers could lead you to millions of pounds in buried treasure.

So, if the Sunday paper’s puzzles don’t feel like enough of a challenge, why not try your hand at some of history’s hardest puzzles?

The Phaistos Disk

The Phaistos Disk is a fired clay tablet inscribed with a ring of unknown symbols believed to originate from the ancient Minoan civilisation on the island of Crete.

Archaeologists believe this strange artifact was made more than 3,000 years ago but its purpose or meaning is a mystery.

When the disk was first discovered in 1908 some scholars believed it was a forgery but most experts now accept that it is a real artefact.

The disk is stamped with 241 prints showing 45 different symbols.

Some appear to portray people or objects such as animals, plants and tools while others are only shapes.

The symbols are grouped into ‘words’ by vertical lines but experts have not been able to figure out what these might mean.

Early interpretations suggested that the symbols might have something to do with an animal sacrifice carried out by a temple on the Island.

Later experts disagreed, with one 2004 study suggesting that the disk could detail a land dispute written in the ancient Luwian language.

However, no interpretation of the symbols is universally accepted and the symbols don’t match any known language on Earth.

This makes the Phaistos Disks one of the oldest unsolved codes in existence.

The Rohonc Codex

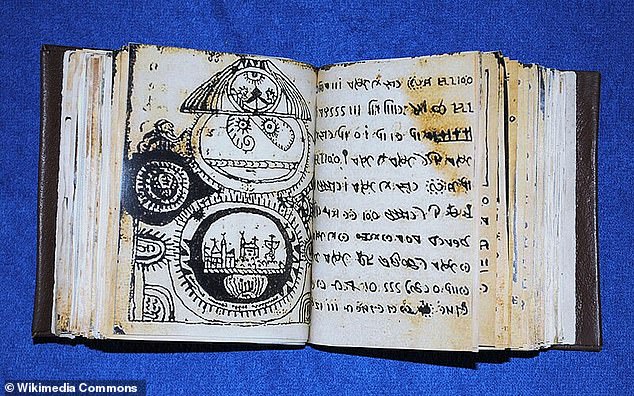

The Rohonc Codex is a 448-page illustrated book which has baffled scholars and historians since its discovery.

The story of the Rohonc Codex began in 1838 when a mysterious manuscript was found in the collection of Count Gusztav Batthyany of Hungary.

Nobody knows who made the book or why but it appears to have been produced in Northern Italy sometime around the 16th century.

Every page has been penned in an unknown script which appears alongside 87 crude religious illustrations.

What makes cracking the Rohonc Codex so challenging is that the alphabet used is extremely long.

The book contains 800 symbols of which about 100 appear with any frequency, far more than in any known language.

This might suggest that the code contains a syllabic language or an entirely artificial language of the author’s own creations.

Interpretations range from a censored religious text to a book of magic spells, or simply an elaborate medieval joke.

However, no one has yet been able to use modern cryptographic techniques to translate any of the text.

This means that historians can only speculate as to why this bizarre manuscript might have been made and what its secret language might contain.

The Shugbourgh Inscription

In the grounds of Shugborough Hall in Staffordshire, an 18th-century monument contains one of England’s most baffling codes.

The structure, known as the Shephard Monument, contains a 10-letter cypher which has stumped historians and cryptographers for hundreds of years.

The mysterious code consists of the letters ‘O U O S V A V V’, framed by the letters ‘D’ and ‘M’ at a slightly lower level.

Above is a mirrored relief of a painting by Nicolas Poussin entitled ‘The Shepherds of Arcadia’, which depicts a woman and three shepherds, with two shepherds pointing towards a tomb.

Above the tomb is the Latin phrase ‘et in Arcadia ego’, meaning ‘I am even in Arcadia’.

The Shepard Monument was built between 1748 and 1763 by Flemish sculptor Peter Schee at the request of British MP Thomas Anson.

However, nobody knows what the letters stand for or whether the monument has a greater symbolic meaning.

Some theorists have tried matching the letters on the monument to the first letters of an acrostic phrase.

For example, some have suggested that the message could be a coded dedication to George Anson’s deceased wife.

It has been proposed that the letters could stand for: ‘Optimae Uxoris Optimae Sororis Viduus Amantissimus Vovit Virtutibus’.

Which translates to: ‘Best of wives, best of sisters, a most devoted widower dedicates [this] to your virtues’.

However, this theory doesn’t explain the letters ‘D’ and ‘M’ and any number of phrases could be found to fit the letters.

Without any further evidence, it is likely that the mystery of the Shugbourgh Inscription may never be solved.

The Beale Papers

The so-called ‘Beale Papers’ first emerged in an 1885 pamphlet of the same name published by prominent Lynchburg citizen James Ward.

The Beale Papers are believed to be the last known clue to a horde of treasure believed to be worth more than $60 million.

As Ward’s story goes, around 1819 a crew of treasure hunters led by Thomas Jefferson Beale uncovered an astonishing haul of 1,360kg (3,000 lbs) of gold and 2,300kg (5,100 lbs) of silver.

Rather than hiding the gold where they found it, the crew shuttled it in wagons over the Blue Ridge Mountains to Virginia, where they buried it in 1820.

Before setting out West on a second expedition, Beale supposedly left an iron strongbox with a Lynchburg tavern keeper, giving him instructions to open the box if he had not returned in a decade.

After 23 years of waiting, the tavern keeper eventually cracked open the box to reveal two letters alongside three pages of unintelligible code.

These pages, which would eventually become the Beale Papers, contain rows upon rows of numbers which modern code breakers recognised as a cypher.

A cypher is a type of code which substitutes letters in a message according to a set of rules usually determined by a specific word or phrase.

When the codes were published, Ward showed how a copy of the Declaration of Independence could be used as a key to crack one of the letters.

However, the key for the last two letters which give away the location of the treasure have not been found, leaving their contents a mystery.

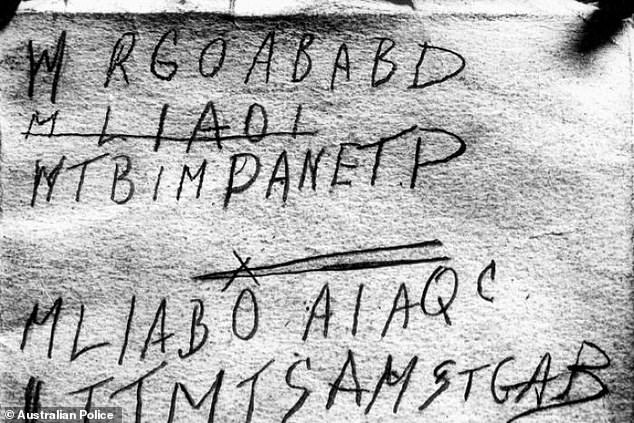

The Tamam Shud Code

On December 1, 1948, Australian authorities found the body of a well-dressed man slumped against the sea wall at Somerton Beach near Adelaide.

The ‘Somerton Man’ had no identifying documents and the labels had been cut from his clothes.

The only evidence detectives could find was a scrap of paper in his pocket bearing the Persian words ‘Tamam Shud’, meaning ‘It is done’ or ‘it is finished’.

This was recognised to be the final line of a collection of a rare collection of Persian poetry called The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.

The police asked the public if anyone had a copy of the book with the last page torn out and, bizarrely, a man came forward saying he had found a copy thrown into the back seat of his car near where Somerton Man had been found.

Not only was the book missing its last page but it was also covered with incoherent writing believed to be some kind of code.

But despite the best efforts of analysts and code breakers, nobody has been able to decipher what this message might mean.

The bizarre details of the case fueled speculation that the Somerton Man may have been a spy or a victim of organised crime.

However, despite countless theories emerging over the years, nobody has been able to decrypt this vital clue which could help crack this 70-year-old cold case.

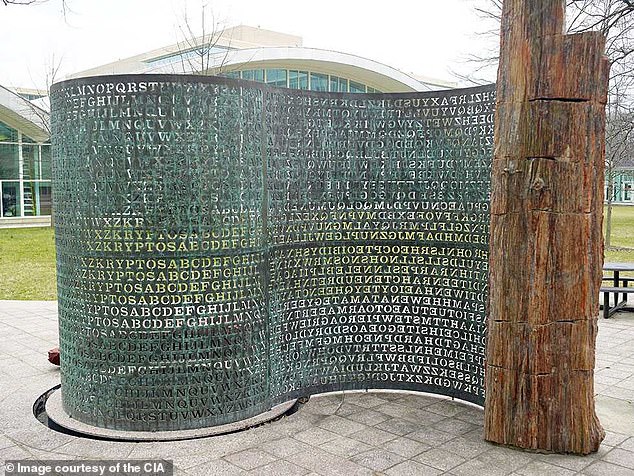

Kryptos

When it came time for the CIA to build its New Headquarters Building in Washington during the 1990s, the agency found itself with a little extra cash in the budget.

That money was set aside for the creation of a sculpture known as ‘Kryptos’ – a large pillar of petrified wood into which an S-shaped copper screen was fitted.

Into this screen, the sculptor James Sanbor carved 1,735 alphabetic letters to create four devious codes.

When looked at from the centre of the CIA’s courtyard, the right of the sculpture reveals four encoded messages while the left shows a ‘chart’ which was used to encrypt the messages.

According to the CIA, Kryptos’ first three messages use a type of code called a Vigeneries Tableaux developed by 16th-century French cryptographer Blaise de Vigenere.

This fairly simple code shifts each letter of the alphabet by a certain amount determined by the contents of the chart.

The first two messages using this code are considered to be relatively straightforward and can be solved by beginner cryptographers.

But the last two are significantly more challenging.

So far, three of the passages have been translated revealing a poem of Sanbor’s own creation, an allusion to something buried, and a passage from archaeologist Howard Carter’s diary describing the opening of a door in King Tut’s tomb.

However, the CIA says that the fourth section has been created with a significantly harder cryptographic method.

So far, even the agency’s best code-breakers have been unable to decypher the final 97-character message.

However, in 2020, Sanborn offered would-be translators a final clue – the word: NORTHEAST.