A first-of-its-kind report has exposed supposedly ‘healthy’ grocery store foods and their toxic ingredients.

Researchers have created the largest database of its kind which ranks tens of thousands of products from Target, Walmart and Whole Foods and scores foods out of 100 based on how processed they are and how many calories and sugar they packed.

Though science hasn’t concluded exactly why, studies suggest the more processed your diet is, the higher the risk of conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure.

The new database reveals a surprising number of food and drinks which look healthy – such as salads, fruit juices, bags of trail mix, and oatmeal – but scored just as bad, if not worse, than some candy and confectionary.

One of the more surprising worst-offenders was a salad from Whole Foods. The own-brand, healthy-looking salad containing brussels sprouts, kale and shaved parmesan scored 93.

The salad contains a host of ingredients including sunflower and canola oil, both of which have been linked to a higher risk of colon cancer.

It also contained 194 calories per 100g serving.

The researchers created the database, which anyone can access online and use to make healthier substitutes, because of there is no easy way for consumers to identify what foods are processed, highly processed, or ultra-processed.

While nearly all foods go through some form of processing, such as washing and packaging, ultraprocessed foods are often made with substances made in a laboratory.

A sophisticated algorithm was used to rate more than 50,000 products out of 100, with a higher score indicating that it is worse for your health.

As a healthier alternative to the Whole Foods salad, the database suggests various options, including an organic packaged salad kit from Whole Foods with just 29 calories per 100g serving and a chicken salad from the same retailer with zero sugar.

These two products had scores of one and 15 respectively.

Breakfast items

Next up, some Quaker instant apple and cinnamon oats from Target have a high score of 99.

The data shows a 100g serving of oats has almost as much sugar as two Reese’s Milk Chocolate Peanut Butter Cups (22g) at 25.6g.

One cup of the breakfast meal also has 372 calories and there are eight different additives listed in the ingredients.

Instead, organic Quaker oats from Walmart boast a score of just six, with a 100g serving containing just 2.5g of sugar and no synthetic ingredients.

There is also just one ingredient in the container (100 percent natural whole grain Quaker quality rolled oats), with no additives.

Breads

Many packaged breads were poorly rated, with a Pepperidge Farm Soft Honey Wheat loaf from Walmart deemed one of the unhealthiest.

The database shows it contains calcium propionate, a food additive used to extend its shelf life.

Studies suggest the preservative could be carcinogenic and it can also cause irritability, restlessness, and sleep disturbance in some children if consumed regularly.

It also has 5g of sugar per two slices and more than 140 calories.

At the other end of the scale, a sliced seven grain loaf from Whole Foods gets an impressive score of just one.

According to the database, an equal serving of this bread provides around 11 calories and 0.6g of sugar.

Fruit juices and energy drinks

On the drinks side of things, diet beverages have some of the worst scores.

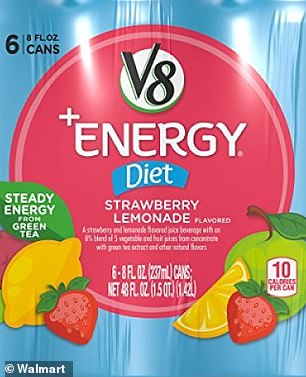

Cans of strawberry and lemonade flavored Diet V8 energy juice drinks from Walmart have a 99 score.

The beverages contain nine additives including the artificial sweetener sucralose, which scientists believe could increase the activity of genes related to inflammation and cancer.

This is in contrast to the healthy claims it advertises.

On its website, V8 states that its drinks are ‘made from fruit and veggies, and give you 80mg of caffeine from tea’.

It adds that they are also ‘rich in B vitamins and made with no added sugar, [so] it’s an energy drink you can feel good about.’

Meanwhile, ‘Great Value’ diet cranberry juice from Walmart gets the maximum score (100) for its poor nutritional value, with five food additives, including sucralose.

A bottle of ‘organic’ apple juice from Target fairs just as badly with 99 out of 100, with a cup containing almost a day’s worth of sugar at 25g.

This is concerning, as children are the main consumers of fruit juice compared to other age groups.

The American Heart Association states men should consume no more than nine teaspoons (36g or 150 calories) of added sugar per day.

For women, they are warned not to consume more than six teaspoons (25g or 100 calories) per day.

One of the healthiest rated juices in the database is a ‘Watercress Warrior’ beverage from Whole Foods with a score of one.

One cup contains 12 calories, 0.8g of sugar and the only additive listed is ‘lemon juice’.

Snacks

Another item with a high amount of sugar is a bag of peanut butter and jelly trail mix from Whole Foods.

A 100g portion contains just over 464 calories and 42g sugar, plus there are 20 additives on the ingredient list.

One of the additives is xanthan gum, which is one of the most commonly used ingredients in ultra-processed foods.

While some studies have linked xanthan gum to health benefits such as weight loss and lower cholesterol, other research suggests it could trigger disruption in the gut and play a role in the development of bowel cancer.

When it comes to ‘smart snacking’, Smart 50 White Cheddar Popcorn from Target gets a score of 98 in the database.

The entry shows that a 100g serving has 464 calories and 10 food additives, including maltodextrin which has been shown to alter gut bacteria.

This compares to a tub of Orville Redenbacher’s Original Premium White Popcorn Kernels from Walmart, with 300 calories per 100g and no additives.

It got a score of one with just one ingredient.

Commenting on the database results, lead researcher Dr Giulia Menichetti said: ‘There are a lot of mixed messages about what a person should eat.

‘Our work aims to create a sort of translator to help people look at food information in a more digestible way.

‘By creating a system of scoring processed food, consumers don’t have to be overwhelmed with excessive and challenging information to be able to eat healthier.’

The database of food items is available to the public via the TrueFood website.

The website features different food categories with a processing score, nutrition facts, and an ingredient tree that shows the makeup of various foods.

The researchers say while Whole Foods offers more minimally processed options, most of the food all of these stores sell is ultra-processed.

There is a system for classifying ultra processed foods, called NOVA, that was developed by Brazilian scientists who first started looking into the topic in the 1990’s.

But there’s a lot of ‘room for interpretation’ in these guidelines, Dr Williams said.

Generally if a food has ingredients you wouldn’t use in home cooking – additives and stabilizers with long names, for example – then it’s probably an ultra processed item.

This system doesn’t classify foods based on the nutritional content within them.

For example, mountain dew is ultra processed, which has next to zero nutritional benefit, but so are many brands of multigrain bread, which contain fiber, vitamins and even some protein.

Over recent years scientists have found that ultra processed foods can increase the risk of cardiovascular problems, diabetes, cancer and a whole host of other nasty health issues, aside from increasing the size of your waistband.

In some stores, highly processed foods were the only option in some categories.

For example, cereals at Whole Foods vary from minimally to ultra-processed.

However, all cereals available at Walmart and Target have a high processing score.

This same trend was seen in the soups and stews, yogurt and yogurt drinks, milk and milk substitutes, and cookies and biscuits categories.

This is because of added sugars and food additives such as flavorings and emulsifiers.

The authors note while grocery stores may sell a large variety in terms of quantity of products and brands, ‘the offered processing choices can be identical in multiple stores, limiting consumer nutritional choices to a narrow range’.

While the data on the TrueFood website is remarkably detailed, it remains limited because it originates from just three stores at a single point in time.

In the future, the researchers say they would like to look at how food options vary in different areas of the country.

Dr Menichetti concludes: ‘People can use this information, but our goal would be to push this to become a large-scale, data-driven tool to improve public health.

‘Most research activities in nutrition still depend on manual curation, but our study shows that artificial intelligence and data science can be used to scale up.’