The UK might not be known for its exotic wildlife.

But you could be unknowingly living next door to one of the dangerous wild animals which are legally owned by private enthusiasts all around the country.

Data shows that more than 2,700 exotic pets ranging from venomous snakes and scorpions to lions and cheetahs are being kept in Britain.

Now, as semi-tame lynx are captured roaming in the Cairngorms, experts have raised concerns that Britain’s hidden zoos could be putting animals and humans at risk.

Earlier this month, two separate pairs of lynx were released near the town of Kingussie, in the Cairngorms National Park.

While the finger was initially pointed at ‘rogue rewilders’, suspicions have now been raised that the lynx could have been released by a private owner.

There are no lynxes legally owned in Scotland, but they might have been owned illegally as part of the UK’s exotic pet black market prior to their release.

Chris Lewis, captivity researcher at animal charity Born Free, told MailOnline: ‘It does suggest that someone was potentially keeping them illegally and no longer wanted them.’

The UK’s exotic pets

The ownership of exotic pets in the UK is controlled by a piece of legislation called the Dangerous Wild Animal Act (DWA).

This law makes it legal to own a surprising variety of exotic animals with relative ease.

As long as you can show the animal can’t escape or cause injury, anyone over the age of 18 can pay £622 to get a licence for almost any animal.

This also means that local councils have accurate records of where to find every legally owned exotic animal in the country.

According to data collected by Born Free, the UK is home to more than 200 wild cats, 250 primates, and over 400 venomous animals, as of 2023.

As this map shows, these animals are often clustered in a few local authority areas with exceptionally high numbers of animals being kept in private hands.

The Southeast of England is the region with the most dangerous animals with 855 different creatures – more than double that of the East Midlands which has the next most.

The Southeast is home to four Bactrian Camels, 133 boars, six lions, four leopards, a vast number of snakes, and many other species.

In Dover, which is home to 74 exotic animals, there are four saw-scaled vipers, believed to be the snakes responsible for the most human deaths due to their aggressive nature.

To see how many dangerous animals are living in your neighbourhood either select your local authority on the map or search using the search tool in the top left.

Scotland’s rogue lynx

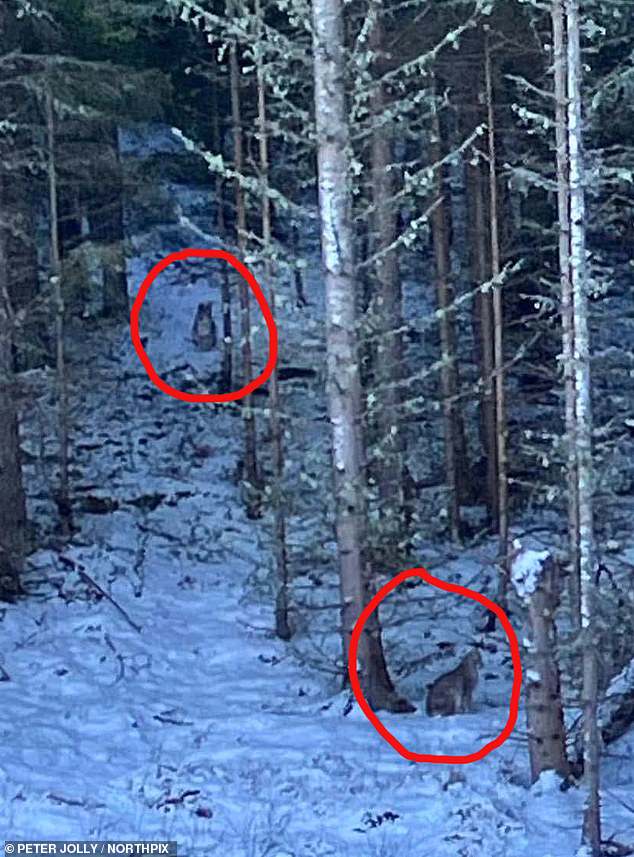

On January 8, residents of the Drumguish area, near Kingussie reported seeing two lynx standing in a layby by the side of the road.

Eye-witnesses reported that the animals were found alongside a number of dead chicks and a large amount of hay.

While the animals were captured overnight by a specialist team from the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (RZSS), another pair were found roaming the area only days later.

RZSS was also able to confirm that these were Eurasian lynx, the largest of all the lynx species.

These fierce predators can grow up to be 55 to 75cm (22-30in) tall and between 90 to 110cm (35-43in) in length – about the size of a large labrador.

While they were once native to Britain, the species was driven to extinction by a combination of hunting and habitat loss between around 1,000 years ago.

Amidst calls to reintroduce ‘keystone species’ like predators, which play a large role in maintaining the ecosystem, the blame was initially placed on rogue rewilders.

It was suggested that an unknown group, frustrated with the slow process of government-backed rewilding efforts, might have illegally released breeding pairs in an attempt to kickstart a wild population.

However, as more information about the animals comes to light, an alternative possibility has emerged.

Instead, some suggest that these might have been released by a pet owner who purchased the lynx on the black market.

Mr Lewis says: ‘It seems that the potential rogue rewilding theory has been put aside and this now suggests that someone was keeping them illegally.’

Where did the lynx come from?

According to data gathered by animal charity Born Free, the UK is currently home to 31 lynx including 21 of the same species found in the Cairngorms.

These could be held in private homes, sanctuaries that don’t have zoo licences or facilities like travelling zoos or animal performance companies which operate under a different licence.

But, since this data was obtained by freedom of information request, it doesn’t contain the details that would show which type of captivity these lynx are in.

However, one striking detail which stands out is that there are no lynx legally owned under the DWA in England.

Likewise, the local authority Highland Council said that no premises in the area had even applied for a licence to own a lynx.

That means that the animals were either transported to the Cairngorms from somewhere else in the country or they were owned illegally.

Mr Lewis says: ‘We have long suspected that there has been non-compliance with the legalisation.

‘With a lynx, you’d obviously hope that people were keeping them outdoors so they would be more publicly visible but, if the land is secluded and there are very few people around, then there’s the possibility that people could be doing it in a non-compliant manner.’

Additionally, the animals were released with little care, simply being dumped by the side of the road in the middle of winter.

According to RZSS, the lynx pairs were released on one of the coldest nights of the year when temperatures dipped as low as -14°C (6.8°F).

Conditions were so poor that one of the lynx died shortly after being brought into captivity by RZSS.

Likewise, the lynx were wholly unprepared for life in the wild and appeared to be semi-tame.

Dave Barclay, the RZSS expert who led the hunt for the lynx told the BBC that the animals were ‘highly habituated to people’.

Mr Lewis says: ‘It certainly suggests that, wherever they had been raised it had been with a high level of human involvement.

‘Especially as they were found incredibly hungry and weren’t able to catch food for themselves suggests they were completely reliant on humans for food; that leads to the suggestion that they were being kept in a private or domestic setting.’

That would appear to make it unlikely for the lynx to establish themselves and breed in the wild.

However, the big question is why someone would release these animals if it wasn’t part of a rogue rewilding effort.

One option is that the lynx were bred in captivity by a private owner who no longer had the space for them.

Mr Barclay, of the RZSS, previously told MailOnline: ‘By their behaviour, we believe they are all from the same litter or at least related. All four are of a similar age and are young Eurasian lynx.’

Although this does fit with the idea that they had been bred by a private owner, there are still many questions to resolve.

‘It’s also very confusing because they are not a cheap animal to purchase,’ says Mr Lewis.

‘For anyone who no longer wanted them, you would think that they would first try to sell them before releasing them.’

However, these details only add to the mystery of where these lynx came from and why they were released.

Steve Micklewright, chief executive of Trees for Life which is part of the Lynx to Scotland charity partnership, told MailOnline: ‘No one knows the motives behind the dumping of the four lynx or the source of the unfortunate animals, but we hope the police investigations will get to the bottom of this wildlife crime.

‘Some people are suggesting this was an attempt at an illegal release, others that the lynx were unwanted pets perhaps obtained through a black market for exotic animals. Right now, this is all speculation. ‘

How animals are being put at risk

The case of the Cairngorms lynx is another example of how the desires of private animal enthusiasts don’t always align with the animal’s best interests.

Proponents of rewilding point to the positive impacts that reintroducing predators like lynx can have on the environment.

A study has suggested that the Scottish Highlands can support 400 lynx where their scent marking would help herds of deer keep on the move and limit overgrazing.

However, uncontrolled releases threaten to disturb existing ecosystems and turn popular opinion against future rewilding efforts.

Prominent champions of rewilding like TV presenter and conservationist Chris Packham have strongly criticised the culprits.

Mr Packham said the actions of the individual or individuals behind the illegal release go against everything people who are serious about reintroduction are trying to do.

‘I’m really cross about it; it does not serve our purposes,’ he added.

Whoever released the lynx and for whatever reason, what is clear is that they had almost no chance of survival on their own.

‘This sorry saga illustrates why illegal animal abandonment like this is so irresponsible and wrong,’ says Mr Micklewright.

‘Reports suggest the tragic death of one of these beautiful, charismatic animals was due to starvation.

‘Simply dumping young lynx, which did not know how to survive in the wild, into the countryside near a lay-by in such harsh weather, was a wildlife crime. Who knows what stress these poor animals went through?’

Likewise, critics point to the large-scale ownership of exotic pets in the UK as an ongoing source of harm for animals.

Born Free argues that the DWA is primarily ‘public safety legislation’ with little focus on how animals are kept beyond avoiding escapes.

While there are some guidelines for how much space or equipment is needed to keep wild animals, there are no species-specific guidelines in law.

This leads to limited protection for pet owners against their own pets and potentially poor standards of living for the animals involved.

Animal rights campaigners have been particularly critical of the fact that the law allows private individuals to keep animals like big cats which require large social groups and expansive territories.

‘There isn’t really any safe or humane way to keep a large cat in captivity privately,’ says Mr Lewis.

‘This provides further evidence as to why the current keeping and trade of exotic pets in the UK needs urgent review.’