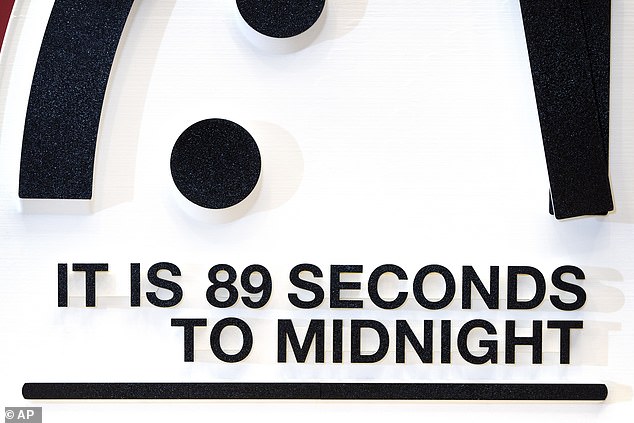

Scientists have outlined the reasons why they believe the world is one second closer to annihilation.

The Doomsday Clock has been unveiled for the first time this year and showed we’re nearer to a world-ending catastrophe than ever before.

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, which decides where the hands are set, moved the timer to 89 seconds to midnight, one second closer than last year – the closest it has ever been in its 78-year history.

They said this reflected the troubling global outlook, with the threat of nuclear war, increasing impacts of climate change and fears over the military applications of AI each contributing to their decision.

Russia‘s ongoing war in Ukraine has increasingly raised fears of nuclear war, while rapid advancements in artificial intelligence have opened the possibility that it could be used to make biological weapons.

Climate change is another existential threat that scientists say the world has failed to tackle, with the devastating LA wildfires this month providing a stark example of how catastrophic the effects of global warming can be.

‘We set the clock closer to midnight because we do not see sufficient positive progress on the global challenges we face,’ said Daniel Holz, board member and physicist at the University of Chicago.

‘Setting the Doomsday Clock at 89 seconds to midnight is a warning to all world leaders,’ he added.

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists created the Doomsday Clock in 1947 during the Cold War tensions that followed World War II to warn the public about how close humankind was to destroying the world.

Since 2023, it has been set at 90 seconds to midnight, but this year scientists predicted it would move forward to reflect the troubling global outlook.

‘The factors shaping this year’s decision – nuclear risk, climate change, the potential misuse of advances in biological science and a variety of other emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence – were not new in 2024,’ Holz said.

‘But we have seen insufficient progress in addressing the key challenges, and in many cases this is leading to increasingly negative and worrisome effects.’

Holz continued: ‘The war in Ukraine continues to loom as a large source of nuclear risk. That conflict could escalate to include nuclear weapons at any moment due to a rash decision or through accident and miscalculation.’

Russian President Vladimir Putin in November lowered the threshold for a nuclear strike in response to a broader range of conventional attacks, a move the Kremlin described as a signal to the West.

Russia’s updated doctrine set a framework for conditions under which Putin could order a strike from the world’s biggest nuclear arsenal.

The Middle East has been another source of instability with the Israel-Gaza war and broader regional hostilities involving countries including Iran.

‘We are watching closely and hope that the ceasefire in Gaza will hold,’ Holz said.

Meanwhile, nuclear-armed China has stepped up military pressure near Taiwan, and nuclear-armed North Korea continues with tests of various ballistic missiles.

Climate change poses another existential threat. Last year was the hottest in recorded history, according to scientists at the UN World Meteorological Organization. The last 10 years were the 10 hottest on record, it said.

‘While there has been impressive growth in wind and solar energy, the world is still falling short of what is necessary to prevent the worse aspects of climate change,’ Holz said.

Last year also saw staggering advancements in artificial intelligence, prompting increasing concern among some experts about its military applications and its risks to global security.

Governments have addressed the matter in fits and starts. In the US, then-President Biden in October signed an executive order intended to reduce the risks that AI poses to national security, the economy and public health or safety.

His successor Donald Trump revoked it last week, and also announced a private-sector $500 billion investment in AI infrastructure.

‘Advances in AI are beginning to show up on the battlefield in tentative but worrisome ways, and of particular concern is the future possibility of AI applications to nuclear weapons,’ Holz said.

‘In addition, AI is increasingly disrupting the world’s information ecosystem. AI-fueled disinformation and misinformation will only add to this dysfunction.’

What is the Doomsday Clock?

The Doomsday Clock is a symbolic timepiece showing how close the world is to a human-made global catastrophe, as deemed by experts. Every year, the clock is updated based on how close we are to the total annihilation of humanity (‘midnight’).

If the clock goes forward and gets closer to midnight (compared with where it was set the previous year), it suggests humanity has got closer to self destruction.

But if it moves back, further away from midnight, it suggests humanity has reduced the risks of global catastrophe in the past 12 months.

On some years, such as 2024, the hands of the clock haven’t moved at all – which suggests the global situation has not changed.

The clock is set by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a nonprofit organization based in Chicago that publishes an academic journal.

Although symbolic and not an actual clock, the organization does unveil a physical ‘quarter clock’ model at an event when revealing if and how the hands have moved.

After the unveiling, the model can be found located at the Bulletin offices in the Keller Center, home to the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy.

Every January, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists reveals its annual update to the Doomsday Clock – even if the hands are not moved.

When was the Doomsday Clock created?

The Doomsday Clock goes back to June 1947, when US artist Martyl Langsdorf was hired to design a new cover for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists journal.

With a striking image on the cover, the organization hoped to ‘frighten men into rationality’, according to Eugene Rabinowitch, the first editor of the journal.

It came amid a backdrop of public fear surrounding atomic warfare and weaponry, just two years after the Second World War ended.

Langsdorf initially considered drawing the symbol for uranium before sketching a clock to convey a sense of urgency.

She set it at seven minutes to midnight because ‘it looked good to my eye’, Langsdorf later said.

On the cover of later issues in subsequent years, the hands of the clock were adjusted based on how close we are to catastrophe.

After the Soviet Union successfully tested its first atomic bomb in 1949, Rabinowitch reset the clock from seven minutes to midnight to three minutes to midnight. Since then, it has continued to move forwards and backwards.

In 2009, the Bulletin ceased its print edition, but the clock is still updated once a year on its website and is now a much-anticipated highlight of the scientific calendar.

Who decides what time to set the Doomsday Clock at?

Shortly after it was first created, Bulletin Editor Eugene Rabinowitch decided whether or not the hands should be moved.

Rabinowitch was a scientist, fluent in Russian, and a leader in the conversations about nuclear disarmament, meaning he was in frequent discussions with scientists and experts all over the world.

After considering the discussions, he would decide whether the clock should be moved forward or backward, at least in the first few decades of the clock’s existence.

When he died in 1973, the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board took over, made up of experts on nuclear technology and climate science, and has included 13 Nobel Laureates over the years.

The panel meets twice a year to discuss ongoing world events, such as the war in Ukraine, and whether a clock change is necessary.

When were the hands furthest away from midnight?

In 1991, following the end of the Cold War, the Bulletin set the clock hands to 17 minutes to midnight.

The end of the war saw the US and the Soviet Union sign the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty.

This meant the countries would cut down their nuclear weapons arsenal, reducing the threat of nuclear war.

Unfortunately, the hands have not been as far away from midnight since then – and they do not look like moving back to this position any time soon.